Every year, hundreds of petroleum industry executives gather in Anchorage for the annual conference of the Alaska Oil and Gas Association, where they discuss policy and celebrate their achievements with the state’s political establishment. In May 2018, they again filed into the Dena’ina Civic and Convention Center, but they had a new reason to celebrate. Under the Trump administration, oil and gas development was poised to dramatically expand into a remote corner of Alaska where it had been prohibited for nearly 40 years.

Tucked into the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, a bill signed by President Donald Trump five months earlier, was a brief two-page section that had little to do with tax reform. Drafted by Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski, the provision opened up approximately 1.6 million acres of the vast Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil and gas leasing, a reversal of the federal policy that has long protected one of the most ecologically important landscapes in the Arctic.

The refuge is believed to sit atop one of the last great onshore oil reserves in North America, with a value conservatively estimated at hundreds of billions of dollars. For decades, the refuge has been the subject of a very public tug of war between pro-drilling forces and conservation advocates determined to protect an ecosystem crucial to polar bears, herds of migratory caribou, and native communities that rely on the wildlife for subsistence hunting. The Trump tax law, for the first time since the refuge was established in 1980, handed the advantage decisively to the drillers.

One of the keynote speakers at the conference that afternoon was Joe Balash, a top official at the Department of the Interior. Balash, who grew up in a small town outside Fairbanks and describes himself as “a local kid,” referred to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge as a “jewel,” and predicted that the entire North Slope region was “about to change in some pretty astounding ways.” The executives were there to hear him talk about what was going to come next: Before development could begin, Interior needed to complete a review of potential environmental impacts, and then get the first leases sold to industry. He recounted for the audience that on his second day on the job—right around when the tax bill was passed—then-Deputy Secretary David Bernhardt sat him down and told him that he would be “personally responsible” for completing the legally complex environmental review process for the wildlife refuge and “having a successful lease sale.”

“No pressure,” Balash said to audience laughter.

The pressure, in fact, couldn’t be greater.

Today, Bernhardt is the secretary of the Interior, driving energy policy in the Arctic and beyond. And although the tax bill gave DOI four years to complete the first sale, top officials at the department, including Bernhardt and Balash, are determined to get it done in half that time, before the end of 2019.

The only thing standing in the way of establishing an oil and gas leasing program is the environmental review process, which includes an assessment of the proposed seismic surveys and an evaluation of the impacts of leasing and future development on the refuge. Environmental reviews are a standard part of oil and gas drilling elsewhere in Alaska, and normally, such impact statements for ecologically sensitive and undeveloped land would take at least two to three years—or even longer, according to three former DOI officials interviewed for this article. Instead, the administration is compressing it into just over one year. The environmental impact statement for leasing commenced in April 2018, and the final results, already publicly available in draft form, are expected to be published next month.

According to interviews with more than a dozen current and former employees at the Fish and Wildlife Service and the Bureau of Land Management in Alaska, that speed has come at a significant cost to the reliability and comprehensiveness of the overall environmental review. They describe a process that has been confusing and “off the rails,” according to one BLM employee. Documents leaked to POLITICO Magazine and Type Investigations reveal that the work of career scientists has at times been altered or disregarded to underplay the potential impact of oil and gas development on the coastal plain. Moreover, DOI has decided it will undertake no new studies as part of the current review process, despite scientists’ concerns that key data is years out of date or doesn’t exist.

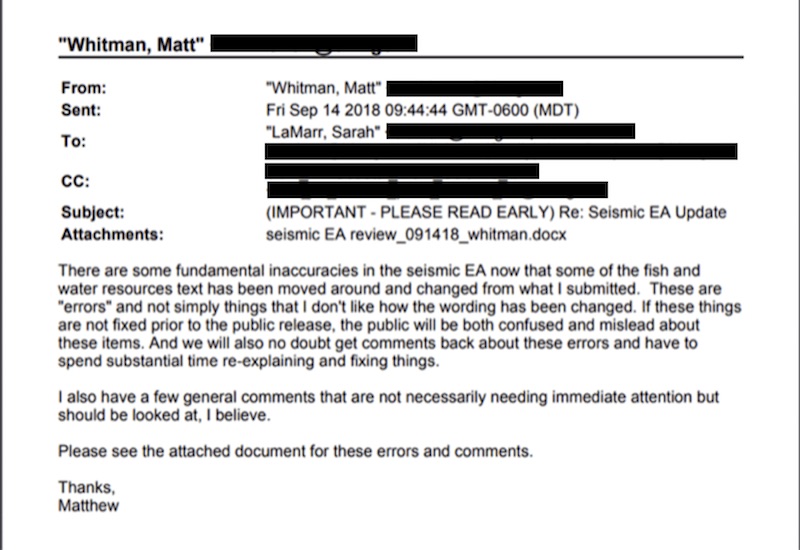

At least two BLM employees, according to the documents, have submitted strongly worded complaints as part of the administrative record alleging that key findings in their work on the environmental assessment for seismic surveys were altered or omitted. In one case, according to the leaked documents, a biologist’s conclusion was reversed from saying the impacts of seismic surveys on polar bears were uncertain or potentially harmful to a finding that the impact would be “less than significant”—an important distinction in environmental law. In another complaint, a BLM anthropologist was surprised to find that large portions of her analysis of potential impacts on native communities had been removed. A third BLM scientist, who studies fish and water resources, noted that “fundamental inaccuracies” had been introduced into his section without his knowledge. Moreover, these same scientists received an email from the district office instructing them not to modify or correct the changes, which were “based on solicitor and State Office review.”

- According to two DOI employees in Alaska, there were internal questions about whether an environmental assessment was sufficient, but DOI leadership insisted on the expedited review.

The conclusions of the environmental assessment for the seismic surveying, which has now undergone numerous revisions, aren’t yet known. But Balash has already signaled the results: In a recent interview with Alaska Petroleum News, he said seismic surveys, a key preliminary phase of development, were likely to take place this coming winter.

In a written statement, DOI did not respond directly to detailed questions regarding who approved the changes made to the environmental assessment and said the analysis is currently on hold while the license applicant revises its plan of operations. BLM Alaska Associate State Director Ted Murphy said, “The Bureau of Land Management Alaska is not aware of any actions by the agency as a whole, or its partners, employees, agents or outside entities to suppress any science; nor has any evidence to the contrary been presented.”

Geoff Haskett, who served as regional director for the Alaska Region of the Fish and Wildlife Service during the Obama administration, said the rush to lease has undermined the scientific integrity of the review process. “In the time they’ve allotted there’s no way they can meet all the legal requirements to do an [environmental impact statement] that’s this complicated and this big and this important,” Haskett said. “They’re going to make mistakes and there will be legal ramifications.”

Why the hurry? Observers point out that the tax bill’s drilling provision is at huge political risk: If Trump is defeated next year, a Democratic administration would almost certainly move to reverse any effort to drill in the wildlife refuge, which is a far easier task if no leases have been granted. In fact, the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives has already introduced legislation repealing the section of the 2017 tax bill that opens the refuge. Getting a lease issued quickly may be the only opportunity to achieve what no other Republican administration has been able to do: secure leases for drilling in the refuge.

“Balash is there to follow through on the Murkowski legislation and to get at least one lease sale done in ANWR so that whatever else happens in the future with policy, there will be pre-existing rights,” a former DOI official who knows Balash told me.

A rushed and incomplete review poses a hazard not just to the ecosystem, but to the companies that want to develop it: The less accurate the information, the less they can protect themselves against risks from their operations. More sophisticated and experienced companies have even been known to ask federal agencies to spend more time on an impact statement if they have concerns that the agency might be overlooking something of consequence. Asked about the draft environmental impact statement for leasing in the coastal plain, an Interior official with experience working in Alaska said, “Unless there are some significant changes made, our feeling is it’s going to be very susceptible to litigation.”

Like many officials inside and outside Alaska, Balash sees opening ANWR as long overdue. And Trump is just trying to make good on a promise that has been made by multiple presidents before him. “The timeline is ambitious, but I think it’s an indication of the priority this administration puts on the effort,” Balash told me at a meeting in February in Kaktovik, the only North Slope municipality located within the refuge boundary. It could take years, even decades, before actual drilling happens. In the National Petroleum Reserve, a major drilling area also on the North Slope, nearly 20 years passed, he said, between the first lease sale and full-scale oil and gas production.

“Is it going to take that long?” Balash said. “Who knows? The first step is we’ve got to have a lease sale.”

The view from Kaktovik.Image: Sylvain CORDIER/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

A Battle from the Beginning

To fly over the unbroken boreal forests of the Alaskan interior, the mostly nameless peaks of the Brooks Range—the northernmost extension of the Rocky Mountains—and the ecologically fragile lagoons and salt marshes of the coastal plain is to see a place scarcely impacted by human development. Even in a state with more than 100 million acres of protected land, the refuge seems to stand apart. Jimmy Carter once called it “America’s last truly great wilderness.”

The 19.6 million-acre wildlife refuge was created by Carter in 1980, when he signed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act. The Act established strong protections for most of the refuge, but gave Congress more discretion over the fate of the coastal plain, a narrow stretch of remote tundra that abuts the Arctic Ocean and where the oil reserves are concentrated.

Environmental science has been guiding development on federal lands in Alaska for decades, not just in wilderness areas, but even in those with active drilling. Since the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in 1970, Bureau of Land Management has routinely carried out environmental reviews of proposed development, including a large percentage of the region’s oil rich North Slope. The purpose of the reviews is not to prevent drilling but to ensure that it’s done with a minimum impact on the environment and Native communities. BLM employees are accustomed to working for Republican and Democratic administrations with different policy agendas.

Fran Mauer was involved in some of the early analysis of draft legislation that led to ANILCA in the 1970s, and went on to work as a caribou biologist at the Fish and Wildlife Service for more than two decades until his retirement in 2002. Mauer, who has a deep, gravelly voice and the weathered look of someone who has spent much of his life outdoors, grew up in the Midwest but has lived in Alaska for nearly 50 years. Over that time, he has seen Washington policy seesaw from more protective administrations to those pushing hard for more drilling, sometimes in disregard of science. When I met him at a café in Fairbanks earlier this year, he came prepared with a stack of documents and newspaper clippings detailing efforts by previous administrations to mischaracterize science or undermine FWS authority in order to advance a pro-development agenda.

Caribou graze on the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, in front of the Brooks Range.Image: USFWS | Wikimedia Commons

The Fish and Wildlife Service has the congressionally mandated authority to oversee the refuge, but as an agency focused on managing and protecting wildlife, the FWS has often been at odds with Republican administrations interested in developing the coastal plain. As early as 1981, Interior Secretary James Watt issued a memo trying to strip the FWS of its authority to oversee the first environmental impact statement and assessment of the area’s oil and gas reserves, and hand it to the United States Geological Survey, which has historically had closer ties to the energy industry. At the time, the conservation group Trustees for Alaska sued Watt over what it viewed as a brazen power grab. Several months later, a U.S. district court judge in Alaska declared the order invalid and described Watt’s effort as “a clear error of judgment.”

In 1987, a 208-page assessment—published with input from more than three dozen FWS scientists, including Mauer, and done in consultation with USGS and BLM—provided the first comprehensive overview of the refuge’s natural resources and the potential impacts of oil and gas development on the region. The report found that oil and gas activities would have significant impacts on wildlife, including the 180,000-strong Porcupine caribou herd, which migrates hundreds of miles to use the coastal plain as a calving ground. FWS also concluded that development would have a “major adverse effect on subsistence lifestyles” of Native communities and that the “wilderness character of the coastal plain would be irretrievably lost.”

The Reagan White House saw it differently. Despite the FWS findings, Interior Secretary Donald Hodel called on Congress to open all of the coastal plain to development. He described the refuge as “the most outstanding onshore frontier area for prospective major oil discoveries in America.”

In 2001, in the wake of 9/11, Republicans renewed their efforts to open the refuge, casting the push for energy independence as a matter of national security. Then-Sen. Frank Murkowski (Lisa Murkowski’s father), who was chairman of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, decided to revisit the issue of the potential impact of drilling on the Porcupine caribou herd. The Gwich’in nation, an indigenous people whose more than 6,000 members live in villages scattered along the refuge boundary in the U.S. and Canada and view caribou as central to their way of life, describe the coastal plain as “The Sacred Place Where Life Begins.”

As one of the refuge’s senior biologists, Fran Mauer was asked to provide data and analysis in response to several of Murkowski’s questions; but he later learned that the conclusions relayed to Murkowski’s office had been substantially altered without his input and that other key information had been omitted from the final version. Mauer’s research showed that concentrated calving took place within the coastal plain during 27 out of the 30 years for which data was available. After working its way up the chain of command to Interior Secretary Gale Norton’s office, however, Mauer’s text was reversed to say that concentrated calving took place primarily outside of the coastal plain, suggesting that the region was not especially critical to the survival of the herd. According to Mauer, the data he provided was also modified to reflect far less frequent use of the birthing grounds.

David Bernhardt, who was then Norton’s congressional affairs director, was reportedly involved in rewriting the answers: Documents showing the difference between Mauer’s analysis and the final version were leaked to Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility and the Washington Post in October 2001. In response, Bernhardt, in a letter to then-Sen. Joe Lieberman (D-Conn.), claimed that the department had simply made a clerical mistake. But he added: “Scientists can and do disagree. There are often areas of interpretation and judgment.” Mauer says shortly after the episode he spoke to a high-level Fish and Wildlife Service employee in Washington, who told him that Bernhardt was “extremely vexed over the leak.” Several months later, a vote to open the refuge to development fell short.

In May 2017, just days before Bernhardt’s confirmation hearing as deputy secretary of the Interior, the scandal over the caribou data resurfaced. In a news release, PEER, the same group that had blown the whistle in 2001, said Bernhardt had played a central role in the affair and called for a Senate investigation before considering his nomination. PEER’s then-executive director, Jeff Ruch, said Bernhardt had an “unfortunate affinity for alternative facts” and accused him of “political manipulation of science.”

At his confirmation hearing, Bernhardt said a number of different entities were involved in drafting Secretary Norton’s responses and that his office in particular was engaged “at each stage and ultimately transmitted the testimony to the [Murkowski’s] Committee.” Bernhardt also added that he was not the primary policy adviser on the wildife refuge.

As deputy secretary and now secretary, Bernhardt is shaping that policy. When the tax bill was finally passed several months after Bernhardt’s confirmation, it effectively removed the Fish and Wildlife Service from having any meaningful involvement in establishing the oil and gas leasing program.

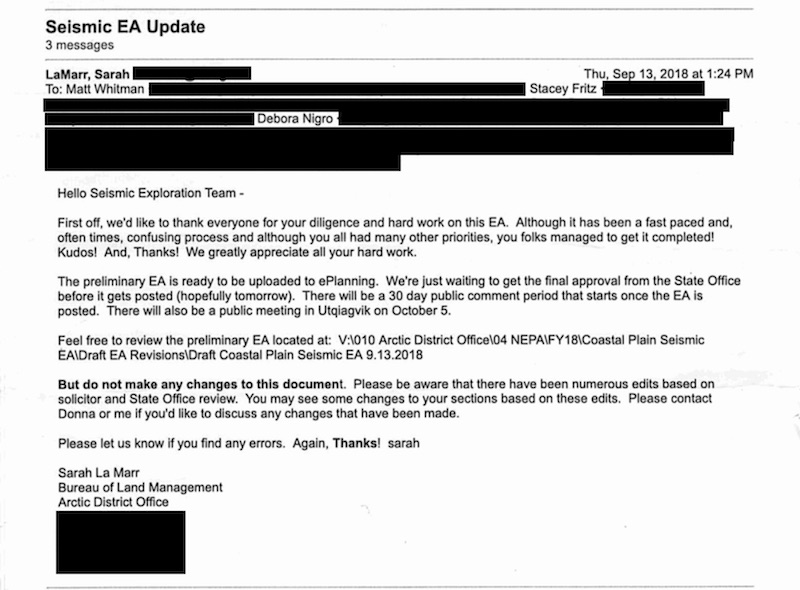

In a September 13, 2018 email, Sarah LaMarr, assistant manager of the BLM’s Arctic District Office, informs the seismic team that the preliminary environmental assessment is ready to be uploaded to the bureau’s NEPA website and that a 30 day public comment period will follow. After thanking the BLM staffers for their hard work, she tells them not to “make any changes to this document,” which has been edited based on solicitor and State Office review. Upon reviewing the new draft, three BLM employees found that significant changes had been made to their text. The EA has undergone numerous revisions but still has not been made public.Image: Adam Federman for Type Investigations

While previous bills seeking to develop the coastal plain, in 2002 and 2005, had given FWS a direct role in co-managing the program and would have granted the service greater decision-making authority, Senator Murkowski’s version omitted any reference to FWS. Instead, it granted exclusive authority over the leasing program to the Bureau of Land Management, which historically has had no jurisdiction over the refuge. “Right now the Fish and Wildlife Service director, acting director or even assistant secretary for the agency, does not have any involvement in the development of this EIS or decision making process,” an FWS employee told me. “Everything is done by Joe Balash.”

Though FWS is technically a cooperating agency on the environmental impact statement, none of its staff scientists were included as part of the interdisciplinary team charged with drafting the document. Throughout the review process FWS scientists, in particular those who work at the refuge, have been largely sidelined. “Here we find ourselves outsiders,” one refuge staffer told me.

In a written statement FWS Alaska Regional Director Greg Siekaniec said the service’s technical and subject matter experts were involved in the review process and “provided comments to BLM that reflected the input of this broad team.”

The Alaska delegation has also successfully installed pro-development allies in key positions at BLM. Steve Wackowski, a former campaign aide to Lisa Murkowski, was named by former Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke as senior adviser for Alaska affairs. Chad Padgett, a longtime former aide to U.S. Representative Don Young (R-Alaska), was recently named Alaska BLM state director. According to a story in E & E News, he was “handpicked” by Balash. Joshua Kindred, a former AOGA attorney, is now a DOI solicitor in Alaska. Meanwhile, FWS refuge staff has dwindled, due to a combination of early retirements and transfers, and is at its lowest level in years. Until recently there were five vacancies at the refuge and the main office in Fairbanks has been without a botanist and aquatic ecologist for more than a year.

Pat Pourchot, who served as special assistant to the secretary for Alaska affairs at Interior during the Obama administration, said Fish and Wildlife should have played a much larger role in the review process and that he doubts the department can complete an environmental impact statement that meets the legal requirements under federal environmental rules in such a short period of time.

“FWS is chafing that they do not have a bigger role in an area that they are charged with managing,” Pourchot told me.

Conclusions First, Science Second

At the Fairbanks office of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, the walls are lined with large format photographs of the remote rivers and valleys of the Brooks Range and panoramic shots of caribou crossing the coastal plain. An old banner celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act, passed in 1964 and inspired in part by the early effort to protect the refuge, hangs from the reception desk. Another poster describes the refuge as “a symbol of wildlife and wild places, now and for the future.”

Fish and Wildlife Service scientists, many of whom work at this office, have historically played a central role in advocating for and expanding refuge protections, even recommending in 2015 that the coastal plain be designated as wilderness. But the new law effectively changed the overarching mission of the Refuge. With the stroke of a pen, the tax act established an entirely new purpose for the Refuge—to “provide for an oil and gas program on the coastal plain.”

“It felt like the world got turned upside down,” one FWS employee told me.

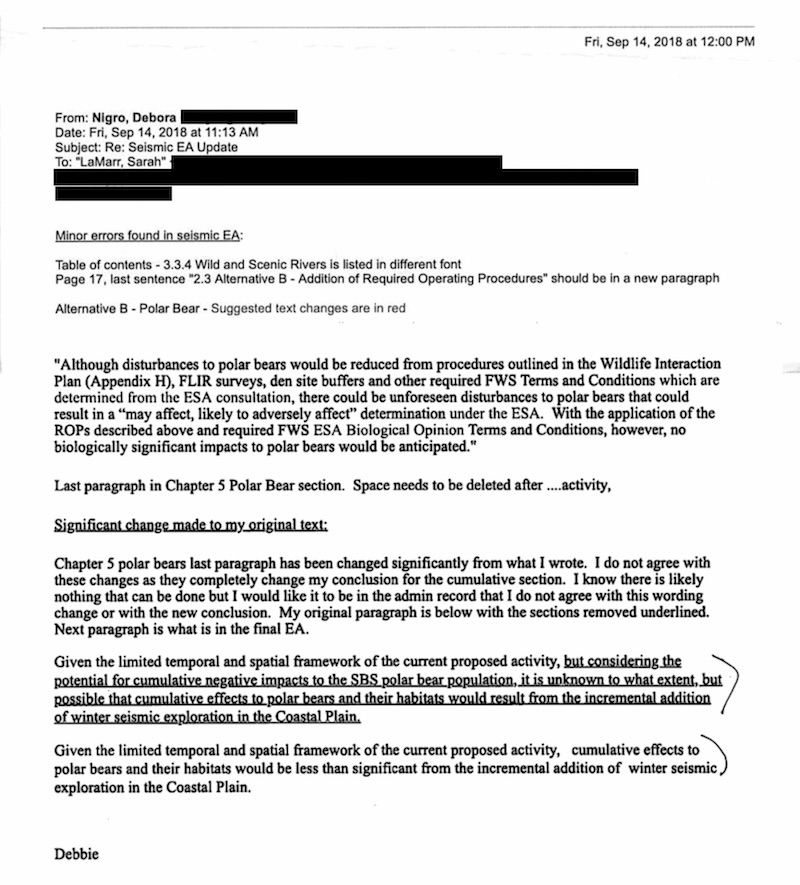

BLM wildlife biologist Debbie Nigro points out that her analysis of impacts to the southern Beaufort Sea polar bear population has been changed significantly and that she disagrees with the new conclusion. Originally Nigro had written that it was possible that seismic surveys of the coastal plain could have “cumulative effects to polar bears and their habitats.” This was changed to say the opposite—that cumulative effects to bears and their habitats would be “less than significant.” “I do not agree with these changes as they completely change my conclusion for the cumulative section,” Nigro wrote.Image: Adam Federman for Type Investigations

Oil drilling often relies on seismic surveys, a highly involved process that itself requires significant development. The last time seismic surveys had been done was in the mid-1980s. In 2014, when Balash was acting commissioner of the Department of Natural Resources, the state of Alaska sued Interior over the department’s refusal to allow seismic surveys of the coastal plain. David Bernhardt, then a lawyer with Brownstein Hyatt Farber & Schreck, represented the state in its unsuccessful bid. Now, Balash and Bernhardt were calling the shots.

Even before the tax act was passed, the Interior Department was looking at ways to change FWS regulations in order to allow seismic surveys in the refuge, according to one Interior employee who was present at meetings during which the issue was discussed. Though seismic technology has changed considerably since the 1980s, surveys of the coastal plain would still have wide-ranging impacts on vegetation and permafrost, according to an independent analysis by the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geobotany Center. “There will likely be significant, extensive, and long-lasting direct, indirect, and cumulative impacts of 3D-seismic to the…permafrost and vegetation of the 1002 Area,” the authors wrote.

The initial BLM timeline for approving seismic surveys was wildly ambitious, even by the standards of this administration. Liz Klein, associate deputy secretary of the Interior during the Obama administration, said the sensitivity surrounding the refuge and the presence of threatened and endangered species on the coastal plain should have compelled a more thorough environmental impact statement. In order to begin surveys during the 2018-19 winter season and obtain data in advance of the lease sale, however, Interior initially pushed to complete its part of the review in just a few months. Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, FWS was also required to conduct its own review of the application and issue a permit to ensure that seismic surveys would not do further harm to the threatened southern Beaufort Sea polar bear population.

In May 2018, SAExploration, a Houston, Texas, oil and gas company, formally submitted an application to conduct surveys of the coastal plain, which would require the use of heavy industrial machinery, the construction of ice roads, temporary landing strips for aircraft, and hundreds of workers housed in camps across the leasing area. Two months later, BLM announced that it would publish an environmental assessment—a less rigorous analysis than an environmental impact statement. Even before it had heard from its scientists, the agency had stated publicly that seismic surveys would have no significant impact.

According to two DOI employees in Alaska, there were internal questions about whether an environmental assessment was sufficient, but DOI leadership insisted on the expedited review. In an email obtained by POLITICO Magazine, the assistant manager for the BLM Arctic district office described the effort as “fast paced and often times confusing.” Another BLM employee who worked on the assessment told me they had “never seen something so off the rails in my life.” The lack of transparency has been compounded by a culture of fear and intimidation, according to current employees of Fish and Wildlife and BLM; even former employees are reluctant to speak on the record because they believe that doing so could jeopardize the careers of their colleagues. “We barely can talk about ANWR with each other,” one BLM Alaska employee told me.

Still, in mid-September 2018, according to documents obtained by POLITICO, BLM was prepared to publish the draft environmental assessment, despite concerns from its own employees and the FWS about potential impacts to polar bears. According to a leaked FWS memo BLM was preparing to publish the draft “as early as Monday September 10th, with a provisional Finding of No Significant Impact.” On September 13, Sarah LaMarr, assistant manager of the BLM’s Arctic District Office, informed the BLM seismic team that BLM hoped to post the preliminary draft of the document to the department’s NEPA website the next day. A 30-day public comment period would follow, and BLM had even set a date for a public meeting in the North Slope city of Utqiagvik on October 5. This would leave enough time for SAExploration to begin seismic surveys as early as December or January, when the ground is thoroughly frozen and can support heavy machinery.

Up to this point, the environmental assessment had received a level of attention reserved for only the most sensitive internal documents, according to two BLM employees. “That EA—every word of it—was the most scrutinized, politicized and controversial thing any of us had ever seen,” one of those BLM employees told me.

On the eve of publication, members of the BLM seismic team were given one last chance to review their respective sections but also instructed “to not make any changes to this document.” After thanking the team for its diligence and hard work, LaMarr wrote, “Please be aware that there have been numerous edits based on solicitor and State Office review. You may see some changes to your sections based on these edits.”

In some cases, the changes were deeply troubling to those who had originally drafted the document. At least two BLM employees took the unusual step of submitting complaints, which become part of the administrative record, an internal way of documenting the decision-making process for NEPA reviews. This sort of forceful condemnation of changes made by higher-ups within the department is rare, though not unheard of, according to Klein, who served at DOI under Obama.

In one instance a fisheries biologist wrote in an email to the project managers that, as a result of changes to his text, there were “fundamental inaccuracies in the seismic EA.” Another career employee was surprised to find that entire paragraphs on potential impacts to native communities, including environmental justice concerns, had been scrubbed from her analysis. “I am troubled by numerous omissions from my sections,” the employee wrote. She also warned that BLM might not be complying with guidance on tribal consultation for the EA. “[BLM] normally conduct government-to-government consultation for large seismic projects in the NPR-A, therefore doing so would not have been extraordinary,” she wrote.

Perhaps the most dramatic change was the reversal of a conclusion reached by Debbie Nigro, a BLM wildlife biologist, who found that seismic activity could have a negative cumulative impact on the southern Beaufort Sea polar bear population. Nigro, a long time BLM biologist who has received recognition for her work to protect threatened waterfowl, wrote the section in consultation with marine mammal experts at the FWS.

Polar bears are an important regional predator, as well as one of the best-known symbols of Arctic wildlife, and they’re considered a threatened species: The southern Beaufort Sea population has declined by more than 40 percent to just 900 bears in the past few decades. Based on SAExploration’s initial proposal, Nigro and FWS concluded there was a real possibility that polar bears and their critical denning habitat would be harmed by winter seismic exploration. According to Nigro’s assessment, “It is unknown to what extent, but possible that cumulative effects to polar bears and their habitats would result from the incremental addition of winter seismic exploration in the Coastal Plain.” Yet after undergoing “solicitor and State Office review,” according to the email from the assistant manager of the Arctic District Office, the section was changed to say the opposite. The draft version stated that if seismic exploration moved forward, “Cumulative effects to polar bears and their habitats would be less than significant.”

In her comments submitted as part of the administrative record, Nigro described the textual change as “significant” and included a copy of her original paragraph alongside the new version. “I know there is likely nothing that can be done,” she wrote, “but I would like it to be in the admin record that I do not agree with this wording change or with the new conclusion.”

In a third email, Matt Whitman, a BLM fisheries biologist who analyzed impacts to water resources, says that “fundamental inaccuracies” have been introduced into his text. These changes, he said, could be misleading and confusing to the public. Whitman was especially troubled to learn that he had not been consulted or informed of the changes before seeing the draft version.Image: Adam Federman for Type Investigations

The Department of the Interior says the draft environmental assessment was not reviewed by the department’s lawyers in Washington, D.C., or by Bernhardt. Nor was Bernhardt aware of the changes made to the document, according to DOI. In addition, the department said BLM’s “approach was predicated and dependent on the presumption that the applicant would be able to” receive the necessary approvals from the FWS. “This never came to fruition and thus the BLM could not move forward.”

Asked whether Balash had reviewed the draft analysis and was aware of the changes made to the document, DOI did not provide a yes or no response. His calendars show he was very much engaged with ANWR issues. Between August 23 and September 13, when Sarah LaMarr sent out her email to the seismic team, Balash had no fewer than nine meetings related to the Arctic Wildlife Refuge. He was also traveling in Alaska in late August and, according to his calendars, had a meeting with regional solicitors to discuss coastal plain matters.

Klein said the documents raise “significant questions about interference with scientific integrity processes at Interior and with the expert conclusions of the department’s own staff. Their work has been changed in ways they don’t agree with. That’s unusual and very troubling.”

The Final Report, But Not the Last Word

Even without drilling, the Refuge is already undergoing profound changes.

Climate change is warming the Arctic nearly twice as fast as anywhere else in the world, setting in motion changes that have alarmed scientists who study the region. As sea ice has diminished greater numbers of polar bears have been forced to come inland to den along the coastal plain. This has led to more encounters between humans and bears and the deterioration of the overall health of the bear population. The southern Beaufort Sea population was listed as a threatened species in 2008, which is part of the reason that FWS has resisted approving permits for ecologically risky seismic surveys. Over the next 30 years, scientists fear that the population could be driven to extinction.

In early February, I flew to Kaktovik, population 250, to attend a public hearing on the draft Environmental Impact Statement for leasing the coastal plain. The much-anticipated document had been published on December 20, two days before the government shut down.

Like the environmental assessment for seismic surveys, the draft EIS for leasing, which evaluates the potential impact of leasing on everything from polar bears and caribou to water resources and vegetation, had been produced with unusual speed, in about eight months. The required public hearings commenced less than one week after DOI announced that they were taking place so there was very little advance notice. Robert Thompson, a polar bear guide in Kaktovik and an outspoken opponent of oil and gas development who follows the issue closely, learned about the meeting when I called him a few days before the hearing. “How do you have this meeting if no one knows about it?” he said.

I had attended the first hearing in Fairbanks the day before, when activists holding Defend the Sacred placards protested that the format for the hearings reflected the department’s lack of transparency and its desire to stifle public participation. DOI had announced that the meetings would be “open house” style with subject matter experts on hand and that comments would be taken only by court reporters or in writing. I watched as activists seized the podium and, for the next two and a half hours, I listened to dozens of speakers, all of them opposed to developing the refuge, make their case. At one point, Balash, who in his introductory remarks acknowledged that there were “strong feelings on both sides of the issue,” conceded that DOI had lost control of the meeting.

Kaktovik proved to be friendlier terrain for the officials from Interior. About 30 residents gathered at the local school, which had recently received a $16 million upgrade, including a new basketball gym, largely funded with oil and gas tax revenue. At least half the population of Kaktovik supports the opening of the refuge and two native corporations—Kaktovik Iñupiat Corporation and the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation—stand to benefit financially if the coastal plain ever becomes a producing oil field. (ASRC and KIC, along with SAExploration, have formed a joint corporation to conduct the seismic surveys of the refuge.)

But in order for that to happen, a considerable amount of infrastructure, including barge landings, docks, spill response staging areas, and road and pipeline connections, will be required. Steve Amstrup, a former USGS polar bear researcher who is now chief scientist for the conservation group Polar Bears International, is doubtful that this sort of development can happen without doing further harm to the species and its remaining habitat. “The developments and associated activities described in the [draft environmental impact statement] are sure to accelerate ongoing declines in the SBS polar bear population,” Amstrup wrote in a comment letter submitted to the BLM. (A request by POLITICO to speak with the U.S. Geological Survey’s lead wildlife biologist studying polar bear population dynamics in the region was denied.)

The morning after the meeting, I borrowed an old Chevy Suburban with a cracked front windshield and, along with a wildlife photographer and a documentary filmmaker, drove out onto the narrow stretch of land where a polar bear had been seen the day before. It was just after 9:30 a.m. and the sun was coming up over the horizon, casting everything in a pale blue glow. The early morning coastal fog had not yet burned off and the wooden homes and power lines in Kaktovik were barely visible in the distance. Fishing boats half buried in snow were scattered along the shore of the lagoon. We didn’t see any bears but did encounter tracks, about the size of a dinner plate, which led in a straight line to the center of the city.

Just beyond Kaktovik, extending out in a web-like pattern, is the highest density denning habitat for the southern Beaufort Sea polar bear population. As sea ice continues to disappear, this territory will become only more important to the bears’ survival. And according to the draft EIS, this same habitat happens to overlap with what are believed to be the richest hydrocarbon reserves in the coastal plain and where potentially “the least restrictive development activities would be most likely to occur.” But whatever the risks associated with future development, the Interior Department has concluded in the draft environmental impact statement that with mitigation measures in place the impacts to the declining polar bear population would likely be “negligible.”

In late June, Mauer flew into the Sadlerochit Mountains on the north side of the Brooks Range for a two-week backpacking trip. Now 73, he said this might be his last trip to the coastal plain. “It could be my opportunity to say goodbye to what I’ve always known,” Mauer told me a few days before he left. “Because, unfortunately, with a place like that, when you bring industrial activity in, there’s no going back. It’ll never be the same again in anybody’s lifetime.”

The final draft of the environmental impact statement is expected in August, after which the Interior Department can move forward with a lease sale. Environmental groups say they will consider litigation, and have asserted that the leasing process was driven by “political deadlines” rather than sound decision-making or scientific integrity.

“It’s clear the administration is desperate to jam through Arctic drilling while President Trump is still in office,” said Senator Maria Cantwell (D-Washington), the ranking member of the Senate Commerce Committee that oversees marine fisheries and coastal management. “The entire environmental review process has been a rush job, and its integrity has been undermined by politics. The Interior Department has ignored its legal obligations and the findings of their own career scientists.”

Trustees for Alaska and other conservation groups have called on Interior to go back to the drawing board and redo its analysis. But even if the federal court rules in their favour, it’s unclear whether such a decision would delay or postpone the lease sale.

One thing, though, is clear: For the Trump administration, establishing a foothold in ANWR is paramount. Five days before Fran Mauer arrived in the refuge, Trump told ABC’s George Stephanopoulos that, along with the tax cuts and slashing of regulations, opening up ANWR would be one of his most important and lasting achievements.