The night before Suliani Calderón Nieves was murdered, she drove to her mother’s house in Bayamón, Puerto Rico, to drop off her two kids. The 38-year-old health care worker had begun rediscovering her freedom after a contentious divorce and was headed to an event in town, where she was going to read a poem she had written. As she was leaving the house, her mother, Sonia Nieves, took a moment to admire her daughter’s long black hair, signature red lipstick, and bright smile. “You look very beautiful today,” her mother said. “Yo sé que estoy bien buena,” Suliani cheekily responded. “I know I’m hot.”

When Suliani returned to pick up her kids on the evening of May 17, 2018, the lightness was gone. Her ex-husband, José Vega Nieves, had shown up unannounced at the end of the reading, one of the many times he would harass her following the end of their tumultuous 16-year relationship. Angry, Suliani fought with him over WhatsApp messages, but her mom encouraged her to drop it. In the heated exchange, Suliani threatened to call the police on him.

That night, after she returned to her home with her children, Suliani logged into Facebook and posted another poem. “La vida te golpea… Life hits you, you think you learn the lesson and it hits you again. When the river of misery leaves its channel, it never returns to its current. The stones are painful episodes, more if you get used to their stumbling, you will only allow more sorrows. No one owns our life, and I just want to live it.”

The next morning, a few minutes before 8 a.m., Suliani left her apartment with the kids. Once she’d navigated her car to the street in front of the complex, she noticed she had a flat tire and began driving back to the parking lot. That’s when José showed up and intercepted her. He had been lurking on the road, waiting for her—police believe he had punctured her tires. The 41-year-old pulled a gray Hyundai Accent rental next to Suliani’s Toyota Yaris, blocking her from reentering the lot. As she frantically called her younger brother Jesús, her ex pulled out a gun, broke the driver’s side window, and shot her multiple times. Suliani died instantly. He then turned the firearm around, aimed for his head, and killed himself. Their children, aged 10 and 13, witnessed it all from Suliani’s back seat.

Suliani Calderón Nieves died in a violent year for Puerto Rican women. Intimate partner murders skyrocketed in 2018 in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, after domestic violence killings had decreased between 2014 and 2017. At least 23 women on the island of 3.2 million were killed by their current or former intimate partners that year, causing the intimate partner murder rate to soar to 1.7 per 100,000 women, up from 0.77 per 100,000 in 2017. The domestic violence murder rate for the entire U.S. in 2017 (the latest year for which data is available) was 0.77 women per 100,000—less than half the rate in Puerto Rico in 2018. (This analysis used census data for women over 18.)

The four Puerto Rican government bodies that report on intimate partner violence have not developed a unified reporting standard for this issue. The island’s police, its judiciary, the Puerto Rico Department of Justice, and the Women’s Advocate Office, an independent state agency with the goal of protecting and advancing women’s rights in the island, all log different numbers. In 2019, the police said the number of reported domestic violence murders dropped to 10. But the real numbers are likely to be much higher. The Puerto Rico Police Department (PRPD), in particular, has a history of mishandling domestic violence statistics; it undercounted the murders of women, including those related to intimate partner violence, by between 11% and 27% every year between 2014 and 2018, according to a study on the island’s femicides.

Since 2018, desperate advocates at feminist organizations such as Colectiva Feminista en Construcción, Coordinadora Paz para la Mujer, Proyecto Matria, and Taller Salud have called on the government to declare a state of emergency over the crisis of gender violence, which would free up additional public funds for government agencies to prioritize the issue. The Vázquez administration has argued the step is not necessary.

As Puerto Ricans have faced disaster after disaster post-Maria—including a series of devastating earthquakes and the coronavirus pandemic—the cascading crises have given new urgency to the longstanding problems in how the police and courts respond to domestic violence, along with the underfunding of victim services. And they have highlighted how the government’s misguided response continues to leave the island’s women vulnerable.

When women contact the police, they face myriad issues ranging from delayed responses for 911 calls to police officers who have insufficient training to handle domestic violence calls. Advocates and survivors say that protective orders handed down by the court are rarely enforced, which makes survivors view them as just a piece of paper.

The police department also has its own problem with domestic abuse. Between 2015 and 2019, there were 449 domestic violence complaints against officers. In this period, there was only one trial that ended in a conviction. The island’s 16-year-long recession and financial crisis have led to domestic violence shelters shutting down or offering limited services; Puerto Rico has gone from 13 shelters to nine in the last decade. As of today, there are no shelters offering services to victims in the southern part of the island—forcing those who want to access a safe overnight space to drive between one and two hours to get there.

Suliani Calderón Nieves. Her mother, Sonia, removed images of her daughter from her living space after Suliani’s death in 2018, and only brought out this photograph on request.Image: Erika P. Rodriguez

On March 15, Gov. Wanda Vázquez issued an islandwide lockdown and 9 p.m. curfew to curb the spread of the coronavirus. Within a month, the PRPD registered almost 10% fewer domestic violence complaints than during the same period in 2019. But officials believe the rate of cases could be increasing. “Our experience tells me that because of the situations at home and other reasons, the information about domestic violence victims is not reaching the police,” Lt. Aymeé Alvarado, who leads the PRPD’s domestic violence unit, told local newspaper El Nuevo Día. Nationally, intimate partner violence incidents and murders have increased during the pandemic. The lockdown ended in mid-June.

On September 4, 2019, Vázquez announced she was issuing a national alert which, rather than allocate additional funds, instructed public agencies and private organizations to take proactive measures against gender violence. (Her office did not respond to multiple requests for an interview or a detailed list of questions sent via email.) The administration created a working group made up of government officials, feminist organizations, religious representatives, civic associations, and groups that offer victim services to come up with a plan to fight the escalating post-Maria violence. Nine months later, amid the deteriorating safety situation caused by the coronavirus stay-at-home orders and curfews, no draft of this plan has been made public. One woman who attended the working group meetings said the efforts do not feel serious—one suggestion included creating an education campaign against reggaetón, the massively popular urban music genre. “This is a matter of life and death,” she said.

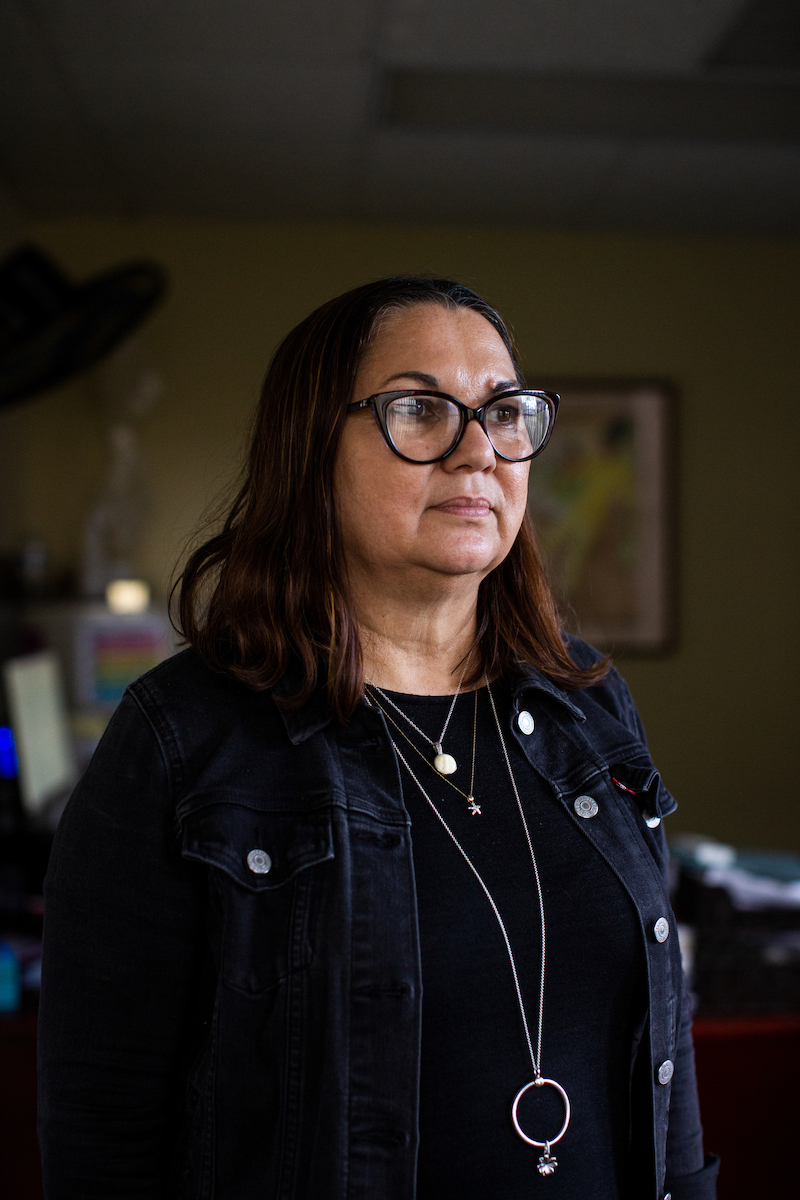

On a recent afternoon, as the sky turned gray, foreshadowing the downpours that often fall in the island during spring, Sonia Nieves sat in her living room, surrounded by angel figurines. No photographs of her daughter graced the walls. The space where she meant to hang a family portrait they took on their last Mother’s Day together is now occupied by a picture of a sunset. Sonia says it is because it remains too painful to look at her oldest child’s face two years after her death.

Suliani Calderón Nieves was born on September 15, 1979, the first of three siblings. An independent girl, she grew up to become a bohemian woman who loved old-school salsa and drinking cheap wine as she wrote poetry. She spent nearly half of her life with the man who would eventually kill her, according to interviews with her mother and her brother Jesús. The couple met when Suliani was a senior in high school in 1997, but they would not start dating until 2001. Around this time, her parents divorced and she dropped out of college in order to work and support the family. By 2004, the couple had their first child, a boy.

Sonia disliked how José Vega Nieves treated her daughter in public, often mocking her intelligence and her appearance. It was not hard to imagine what he could say to her behind closed doors. There were other ways in which he was cruel: When Suliani found out she was pregnant, she planned to tell him in front of her family. She bought baby booties to give him. According to her mom, his response in front of everyone was: “When your belly grows, I’ll believe you.”

Suliani’s brother Jesús believes the psychological and emotional abuse she suffered never escalated to physical violence, though they can never know for sure. In 2005, the situation became unsustainable. Jesús helped her leave the house the couple owned under the cover of night. But the separation didn’t last long. (It can take victims of intimate partner violence an average of seven attempts to leave their abuser.) Suliani would soon become pregnant with her second child, a girl, and the couple went on to marry. In protest, no one in her family attended the wedding.

Sonia believes after her granddaughter was born, the psychological and emotional abuse subsided for a few years. But sometime in late 2016, Suliani decided to end the relationship. She showed up at her mother’s with her two children and their luggage. After getting the kids settled, she hid in her mother’s bedroom. Sonia asked her if she was afraid; Suliani said yes. José kept calling and threatening her, so Sonia called the police. Two officers came to the house, but despite his threats, José never showed up. The separation only lasted a week, however, and the couple got back together.

This is when the “kidnapping” happened. According to Sonia, José took away Suliani’s cellphone, deleted all her social media accounts, and banned her from using her car, insisting he drive her everywhere. The only way Suliani could communicate with her family was using the phone at work. Both Sonia and Jesús begged her to leave her husband for good.

The final attempt to break off the relationship happened in the summer of 2017. Suliani asked her brother Jesús to help her escape again; they packed everything in a rush and got out of the house the couple had shared for more than a decade. Jesús hid José’s firearms, which he legally owned due to his security-related job. The couple got divorced, and soon after, Suliani filed for a protective order against her ex on the basis of harassment and stalking. For a while, José stayed away from her and the kids. But the order expired in December 2017, three months after Hurricane Maria had thrown the island into chaos. Suliani showed up to the hearing without a lawyer, thinking it would not be a big deal. Instead, a judge declined a renewal.

“Jesús, I’m fucked,” she told her brother in tears after the hearing.

Getting help in a machista place like Puerto Rico has often been hard for victims. Right-wing lawmakers and religious groups have outsized influence in Puerto Rican society, constantly pushing for rigid gender roles, which has, in part, caused intimate partner violence to remain a taboo subject to this day. It’s not uncommon to hear from these groups that women lie about being abused to punish their exes, that it is the victim’s fault for not choosing the right partner, or that these issues should be handled internally within the family—undermining domestic violence as a matter of public health.

Island police have a checkered history when it comes to handling gender and sexual violence cases. “The Puerto Rico Police Department’s role is that of a machista,” said Sonia Nieves. “They don’t know why a victim is caught in the cycle.” A June 2012 investigation by the island’s American Civil Liberties Union chapter found the PRPD was systematically failing to protect victims. The failures began at the top: In 2011, Superintendent Emilio Díaz Colón said at his confirmation hearing that intimate partner violence did not fall under the purview of the department. The ACLU found the PRPD neglected to initiate investigations on domestic violence allegations, enforce protective orders, arrest alleged abusers, coordinate with prosecutors, educate victims on their legal options, and address allegations of domestic abuse within the department.

Sonia Nieves at her home in Bayamón. Nieves has become vocal about the Puerto Rican government’s failure to address domestic violence in after losing her oldest daughter in 2018.Image: Erika P. Rodriguez

The organization’s findings were supported by a wide-ranging federal civil rights lawsuit brought against the PRPD by the U.S. Department of Justice in December 2012 that accused the police of excessive use of force, unconstitutional searches, discriminatory practices, and failing to address cases of intimate partner and sexual violence. The suit was settled through a consent decree in July 2013, in which the government agreed to reform the department and overhaul many of its policies.

The ACLU Puerto Rico says many of the issues from its 2012 report are still present today. As part of the reform, the PRPD was asked to take a victim-centered approach in responding to domestic violence calls, update its protocols for cases involving civilians or cases within the force, and adequately collect statistics on intimate partner violence. “Our experience is that even though there are protocols and there’s a consent decree that orders these changes take place, in theory—these are not being fulfilled,” said Johanna Pinette, an associate attorney at the ACLU Puerto Rico.

More than a dozen advocates, survivors, and victims’ family members reinforced Pinette’s claim: Police are often unable to recognize the signs of intimate partner violence and regularly mishandle complaints. The women’s rights coalition Coordinadora Paz para la Mujer has helped develop new domestic violence workshops for police cadets, but its executive director, Vilma González, said the trainings are not enough. As soon as cadets enter the police academy, the curriculum should include a gender lens, said González, and active agents should be required to take continuing education classes. “It’s not like you can take an eight-hour workshop and suddenly become an expert in gender violence,” she said.

The process of investigating these incidents can also be flawed, Pinette said. If the victim is undocumented, police ask about their immigration status, even though it’s not a requirement and could intimidate them into being silent, she added. Organizations that offer shelter and other services to victims say their clients are incorrectly told they’re required to report a violent incident in the police district where it took place. But by law, you can report domestic abuse in any precinct of any district. In the event victims even make it to the investigation stage, the manner in which interviews are conducted can be traumatizing because survivors are often made to feel as though they’ve committed a crime. “We still have cases where police officers are not paying adequate attention to victims,” said Vilmarie Rivera, president of the shelter coalition Red de Albergues de Violencia Doméstica de Puerto Rico. Contacting the police is the “first point of entry into the system,” she said. “But then victims think, ‘I told my story to an officer and they don’t believe me, so what’s going to happen if I appear before a judge? They will not believe me either.’”

Another problem highlighted in the ACLU and DOJ investigations is the sheer number of abusers within the police force itself—and how they are safeguarded from accountability. In recent years, several male officers have killed their current or former intimate partners. There were at least 449 domestic violence complaints brought against police officers (414 men, 35 women) between 2015 and 2019. A little over half the complaints—242—led to arrests, with 225 male officers and 17 female ones being collared by their peers. Out of all of these complaints during this five year period, only one male officer went to trial and was convicted, in 2018. These findings are based on biannual reports the PRPD is supposed to share publicly as part of the consent decree, though reporting on these incidents has been fragmented and inconsistent throughout the years, and there seems to be missing or incomplete information.

“The government’s vision is that there are two or three rotten apples within the police, but it’s not an issue of the institution,” said Zoán Dávila, a lawyer and member of Colectiva Feminista en Construcción. But these are “hundreds of complaints against officers who’ve abused their partners and several cases where officers have killed their partners, some of whom have then committed suicide.”

“The police are not equipped,” said Ada Álvarez Conde, an anti-gender violence advocate and state senatorial candidate. “The law exists. But if the people meant to execute it are not capacitated, have no sensibility, and don’t see this issue as a priority, nothing will happen.”

When police neglect to handle intimate partner violence with the same urgency and interest as other violent crimes, it can put victims in even more danger.

The night M finally broke off her relationship, her abuser had come home high on cocaine and attempted to rape her twice. (Details about M’s identity and location are withheld for her safety.) After he left, she called 911. The police officers who responded to her call helped her leave the house safely, but they failed to initiate the domestic violence protocol. Officers said M had asked for help leaving the house without mentioning she had talked to them about the attempted rape and the previous abuse. M disputes this claim. A subsequent internal investigation by the police precinct maintained that M failed to report domestic abuse when she first called the police and found no wrongdoing.

A picture of Jesus Christ hangs in the home of Sonia Nieves.Image: Erika P. Rodriguez

The PRPD’s protocol on how to investigate incidents of domestic violence outlines what officers must do: Move the victim to a secure area; interview them and any witnesses; call agents to process the scene and gather any physical evidence; arrest the accused abuser on the scene or put out an “attempt to locate” alert; fill out an incident report; and tell victims what is next in the process. The 2012 ACLU report found that when a domestic call comes in, the protocol is often not initiated by officers. Pinette, the ACLU attorney, says the problem continues. As in M’s case, the consequences can be devastating.

M went to court the next day to seek a protective order. She thought there would be a record her call had been related to domestic violence, which she could use to support the protective order request even if police had not taken her to the precinct that night. But she learned from the court clerk there was no such record, since the police had simply registered the incident as a home dispute.

Regardless, M was able to obtain a temporary protective order. After several hearings, a judge granted a permanent order that would last a year. But M soon learned the protective order did not guarantee her safety. A few months after leaving her abuser, M was blow-drying her hair when she looked out of the window and saw he was driving slowly by her house over and over again. Though she could not see inside, she knew the make and model of her ex’s car. “No one else in our town has that car,” she said. Panicking, M called 911.

The police took nearly 40 minutes to arrive. By the time they knocked on M’s door, her abuser was gone and she had finished drying her hair. To this day, M believes the delay could have given him enough time to kill her if he wanted to.

The protective order banned him from coming near her or contacting her in any way. But the officers told her that technically she had not seen the driver so she had no way to prove it was her abuser. Therefore, they could not bring him in for questioning. She told the officers her ex had violated the protective order over and over again—calling her using blocked numbers, texting her using temporary numbers, sending her messages through other people’s phones. The officers told her nothing could be done.

“The system is shit,” she said. She added: “Still today, I’m paranoid. I don’t want my life to depend on what he does or does not do.”

The day before our interview, her abuser reached out to M. The protective order against him had expired a long time ago; she declined to renew it because she saw it as nothing but a worthless piece of paper. M ignored his message.

The Puerto Rico Police Department’s headquarters are housed in an intimidating high-rise next door to Plaza Las Américas, the Caribbean’s largest shopping mall, across the street from the arena Coliseo Roberto Clemente in San Juan. Sgt. Juan Arce Pérez, who has led the PRPD’s Domestic Violence Unit in the Bayamón district for the past five years, is an affable veteran cop who led us through a maze of hallways until we arrived at the floor where the criminal investigations department (abbreviated as CIC in Spanish) is housed. As part of the restructuring brought forward by the consent decree reached between the PRPD and the U.S. Justice Department, the Domestic Violence Units operates under the CIC. Arce Pérez was chatty and offered us a lollipop as soon as we sat down in a large, bland-looking conference room for our interview. He does this candy thing with everyone, he acknowledged.

Despite the criticisms many have about the PRPD’s current handling of intimate partner violence, it’s clear Arce Pérez is a true believer. “The system works. And by that, I mean the police and every other body [that deals with this issue]. That’s why they exist,” he said. “Sometimes, the person that needs to help themselves is the victim. When they call the police, that’s the first step they take to seek help.”

Johanna Pinette, associate attorney for the ACLU in Puerto Rico. In 2012, the ACLU published a report detailing how the Puerto Rico Police Department failed to protect victims of domestic violence and investigate related crimes.Image: Erika P. Rodriguez

The police’s neglect to initiate the domestic violence protocol, as happened with M, was one type of failure the U.S. Department of Justice ordered the agency to fix following its lawsuit six years earlier. The 10-year, multimillion-dollar reform process outlined in the 2013 consent decree has been a bumpy one. Police monitor Arnaldo Claudio was appointed by a federal court to oversee the reform of the PRPD in June 2014, but he resigned in 2019, saying he had lost trust in the process. Claudio was replaced by John Romero, who recently issued a glowing progress report, his first since assuming the role of police monitor. He said the diverse trainings the department has undergone over the past few years have worked, and officials are fulfilling several of the consent decree requests on the areas of procedures, use of force, and technological information. There was no mention of how the department is handling cases of gender violence.

Puerto Rico faces another urgent crisis that has affected the department’s ability to do its job. In 2015, the island’s government announced it had $72 billion in debt it could not pay. President Barack Obama and the Republican-controlled Congress created the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) in 2016 to manage the debt. (Puerto Rico has been an American territory since 1898, and its residents are U.S. citizens.) The legislation established the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico, known locally as La Junta de Control Fiscal, made up by seven unelected members appointed by the president of the U.S. who effectively control Puerto Rico’s finances until the debt is repaid.

The board reduced the PRPD’s budget and has proposed measures such as cuts to the pensions of public employees, including the police. As a result, hundreds of officers left the department for better opportunities in the private sector, blaming the meager pay and the lack of retirement opportunities. Overall, the PRPD’s head count went from 22,000 officers to 12,000 between 2010 and 2017. Then, over 1,700 officers left the force in 2018 and 2019 alone despite a mandated salary increase. These cuts have affected the PRPD’s ability to properly function, including on the issue of intimate partner violence. “These austerity measures affect the issue of gender violence and makes it worse. There’s not enough personnel to attend domestic violence complaints,” said Dávila, from Colectiva Feminista en Construcción.

According to Arce Pérez, every one of the 13 PRPD districts have officers who specialize in domestic violence. He was not able to say off the top of his head how many agents served in each district. He said the PRPD is aware of how gender roles might be more rigid in rural, low-income parts of the island, which means it could be more difficult for victims to reach out for help.

Throughout our conversation, he kept reiterating his confidence in the intimate partner violence protocols and said the police department carefully fulfills its role every step of the way, from the first 911 call to booking an abuser in jail. He argued that any criticism found in the 2012 ACLU report and the DOJ lawsuit has already been dealt with, even when presented with the advocates’ concerns.

“Our policy is to establish the elements of a crime, arrest the abuser, and investigate so we can rescue a victim from a dangerous situation,” he said. He didn’t respond to questions about cases such as M’s and other survivors, saying that without knowing the details firsthand it was impossible for him to say whether something went wrong.

Of the police officers who have been accused of intimate partner violence, Arce Pérez said there’s “zero tolerance.” Agents are disarmed immediately after a complaint is filed, and the cases are brought to a prosecutor.

It’s clear Arce Pérez cares about the issue. He’s nothing like former police chief Díaz Colón, who argued at his confirmation hearing that other agencies are responsible for dealing with intimate partner violence. Arce Pérez views this issue as a matter of public health. “One death alone is regrettable,” he said.

But advocates say these changes don’t reflect the reality on the ground. “What’s the point of having these protocols if the people who must put them in practice don’t know them?” said González, from Coordinadora Paz para la Mujer. “Or they don’t put them into practice when people come seeking those services? Or if there are no consequences for those who fail to put them into practice?”

After M, 23, called 911 on her abusive partner, the police claimed she didn’t mention the incident was related to domestic violence. Instead, it was mislabeled as a home dispute.Image: Erika P. Rodriguez

The latter is a point of anger for survivors like M. One of the reasons she didn’t want to reveal her identity for this piece is that she fears police retaliation. She still blames the police for her abuser’s freedom. But after spending a lot of money and time on her criminal case and handling her trauma, M is moving on, thankful she is alive.

Suliani Calderón Nieves put her faith in the court system. Despite the emotional abuse and threats she endured, she never reported her ex-husband directly to the police. A domestic violence complaint isn’t necessary to obtain a protective order because such orders are civil court tools, according to the law. Violating a protective order, however, is a criminal matter. “If an abuser breaks a protective order, it is a serious felony. That person must be arrested,” said Dávila from Colectiva Feminista en Construcción.

Suliani obtained a protective order against her ex-husband in the summer of 2017 on the basis of asecho, but her request for a renewal was denied in December 2017.

One of the things that makes Suliani’s mother Sonia angry today is that José’s firearms were not permanently removed from his home. The law only allows this to happen when the protective order is in effect or an abuser is found guilty of violating it. When Suliani’s permanent protective order was denied, there was no legal recourse to remove José’s guns. The weapons were one of the main reasons why Suliani was afraid in the months leading up to her murder. Though they were already divorced, José kept trying to get back together. “He could not stand that my sister left him,” said her brother Jesús. “He was a demon.” When her mother Sonia asked Suliani whether she was afraid for her life, she said yes.

Still, Puerto Rico’s court system has taken proactive measures to address domestic violence. In 2007, a pilot program created the Specialized Chamber of Domestic Violence (abbreviated as SEVDs in Spanish) in the San Juan judicial region. SEVDs officially launched in 2010 and handle all criminal procedures related to intimate partner violence. They were modeled after domestic violence courts in the U.S. mainland, which have been growing in number for the past 25 years. The goal of SEVDs is to provide a safe space for victims as their cases are heard. It provides personnel trained to handle cases of intimate partner violence—including judges and court personnel—which can help prevent revictimization. Other features include keeping accused abusers in a separate room from victims, offering child care on-site, allowing for witnesses to testify via closed-circuit TV, and providing a wide range of referrals for services such as psychological help, emergency shelter, and legal representation. Today, there are SEVDs in seven courts on the island. Overall, the program serves about 83% of Puerto Rico’s population. In Utuado, a town in the island’s central mountainous region, there’s a Specialized Chamber of Gender Violence that handles criminal cases of both domestic violence and sexual assault—the first of its kind in all of the U.S. (Two judicial regions, Aguadilla and Guayama, are not part of the initiative at the moment but have specialized personnel on-site to help victims navigate the justice system.)

But as of today, there has been almost no literature studying the importance of SEVDs, and there’s little data on how successful they have been. Advocates are largely skeptical of their effectiveness. “We know that many times when women go to court, when they call the police, or when they show up at a hospital, they don’t receive help in the way they should,” said González, from Coordinadora Paz para la Mujer. Pinette from the ACLU concurred. “Courts, independently of what your case is, are hostile, cold places,” she said. She suggested judges might have the same biases around intimate partner violence as Puerto Rican society at large. “There are judges who are not good. They are meant to be impartial, but they’ll always have flaws,” she said.

Zoan Davila is a lawyer and member of the Colectiva Feminista en Construccion, a feminist political project founded in 2014.Image: Erika P. Rodriguez

Over the years, Coordinadora Paz para la Mujer and other women’s rights groups have demanded greater oversight of the police department and the courts with the objective of improving the services offered to victims. A 2001 law created the Women’s Advocate Office, an independent state agency that allows for legal examination through the lens of women’s rights. But the woman in charge of the office today has been accused of prioritizing partisan loyalty over autonomy.

On the morning of May 18, 2018, attorney Lersy Boria was driving down a road in Bayamón with her son in the back seat when the Toyota Yaris in front of her stopped. She saw a man get out of his car, yell at the female driver in front of her, and pull out a firearm. Then, gunshots. Boria was the only witness to the murder of Suliani Calderón Nieves. She said this horrible act was her motivation to seek to lead the Women’s Advocate Office; she was named to the position of women’s advocate by Gov. Ricardo Rosselló in July 2018. Boria is younger than her predecessors—she was only 38 when she became la procuradora—and her resume prior to her appointment had little to do with women’s issues. But witnessing Suliani’s murder distinguishes her from other government officials; she’s seen the consequences of intimate partner violence up close.

“The issue of domestic violence in Puerto Rico is a multifaceted and multisector issue. Since I became the women’s advocate, and I saw everything we have to work on, [we realized] we need to work on education, accountability, and rehabilitation,” she said.

The Women’s Advocate Office was intentionally created as an independent state agency with broad powers to protect and advance women’s rights in Puerto Rico, one that can work alongside the government but whose leader does not serve at the pleasure of whoever is in power. Some of Boria’s responsibilities outlined in the Ley de la Oficina de la Procuradora de las Mujeres include investigating the infringement of women’s rights, weighing in on the creation of public policy, assessing whether said measures are being adequately implemented, and issuing administrative fines to government agencies that are found in violation of them, including the police. Addressing the island’s gender violence crisis is also one of the office’s explicit duties, according to the law.

In her nearly two years in office, Boria has championed measures meant to help victims of intimate partner violence. Her office has certified mediators who support victims as they move through the legal system. Advocates were troubled by how most rehabilitation programs for abusers on the island were not licensed, and Boria looked into that issue too. Legislation is another area where Boria uses the weight of the Women’s Advocate Office. She pushed for a bill establishing 15 days of unpaid leave for survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault, a measure that was signed into law by Rosselló before he was ousted last summer. She also supported recent legislation to create a special emergency phone number for domestic violence victims.

But Boria has also remained on the sidelines for some critical debates, her critics said. She stayed publicly silent about a law signed by Vázquez in December 2019 that allows for survivors of domestic violence to receive an expedited gun license if they have a protective order. Women’s rights advocates and victims’ services organizations say they were not asked for their input when the legislation was drafted and have opposed it since. They believe Boria should have too. “Arming women does not necessarily make them safer,” said González, from Coordinadora Paz para la Mujer. Research has found gun ownership rates are uniquely tied to domestic homicides in the U.S. Half of the women killed by their intimate partners are fatally shot, and these gun-related murders increased by 26% between 2010 and 2017. Owning a gun poses a challenge for victims who want to be housed in a shelter. “We have to now establish [new security] protocols on how to handle this if they come in,” said Rivera, from Red de Albergues. “These measures might be done in good faith, but they don’t work logistically.”

Vilma Gonzalez is the executive director of the women’s rights collective Coordinadora Paz para la Mujer.Image: Erika P. Rodriguez

Critics argue that when Boria chooses to weigh in on legislation or other measures, she’s too focused on incrementalism and hasn’t been willing to hold accountable the administration of Rosselló, who appointed her to the job, or that of his successor, Vázquez. In late 2018, she said she could not issue a fine to the PRPD for pepper-spraying women protesters at a weekend-long sit-down against gender violence even though it was within her power to do so—a move seen as support for the Rosselló administration.

“She’s not a government employee. The law that created this office offers her autonomy precisely because the job of the women’s advocate is to inspect whether the government is implementing public policy to eradicate violence against women,” said Dávila, from Colectiva Feminista en Construcción. “The women’s advocate should not side with the government, defending how they are handling this issue. She needs to investigate why there are failures, who is responsible, and how they can be solved. That’s not what she’s done.”

There are other concerned parties, too. Rivera, from Red de Albergues, believes there is a disconnect between their needs and the efforts the Women’s Advocate Office has prioritized. Shelters in particular are expensive programs to run—housing a victim with three children costs about $7,500 per month—and they have been hard-hit by the austerity measures born out of the island’s fiscal crisis. It’s unclear if Boria has advocated on their behalf throughout her tenure.

The Women’s Advocate Office specifically manages funding from the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), which shelters can receive. But they have to compete for these funds against other initiatives, including domestic violence training for the PRPD, anti-sexual violence programs, and more. “We’re getting less funds for us to give our services,” Rivera said, adding that’s the case for their other significant streams of government funding: the state legislature, the Administration of Families and Children, and the Puerto Rico Department of Justice. “Ironically, we are the one mechanism that is 100% effective. Women are not killed in shelters because we have security protocols that guarantee victims are protected.”

Boria largely dismissed the complaints about her performance, instead saying different sectors should strive for unity if they want to end violence against women. “We’re all working towards the same goal. We should not focus on rumors. We need to work on a strategic plan and join forces,” she said. “We can’t keep working apart or seeking the spotlight. The important thing is that we all work together and establish the best public policies.”

Women’s rights organizations feel Boria did not join them in the one area where they say her support could have made a difference: Demanding the government declare a state of emergency due to gender-based violence. Instead, Boria stood behind Vázquez as she issued a national alert last September. She has since participated in the meetings of the working group the government established in the fall of 2019 to tackle Puerto Rico’s domestic violence problem.

En la oficina de la coalición Coordinadora Paz para la Mujer.Image: Erika P. Rodriguez

In December, four feminist organizations—El Movimiento Amplio de Mujeres (MAMPR), Colectiva Feminista en Construcción, Taller Salud, and Proyecto Matria—said they would not continue their participation in the working group. Dávila, from Colectiva Feminista en Construcción, said they came to the table willing to work with the Vázquez administration. In the first meetings of the working group, they saw the draft proposed by the government and were allowed to make suggestions.

“It was very broad and vague,” she said. There was no acknowledgment of the system’s failures. It was not a concrete plan.” In December, they received an updated version that did not acknowledge any of the amendments the group had made. “Everyone was like, ‘this is bullshit,’” she said. Colectiva Feminista en Construcción decided to leave the working group, feeling it was a farce.

The remaining members of the working group have reportedly forged on. Vázquez said in early March the final version of the plan would be made public “within weeks,” just as the coronavirus pandemic hit the island. It has yet to happen.

Sonia Nieves, still grieving the death of her daughter, believes the government’s hesitancy to prioritize the crisis is deadly. “I’m sure if one of the governor’s daughters had been the victim of gender violence, she would have already declared the state of emergency,” she said.

The morning her daughter was murdered, Sonia received a call from the precinct asking if she could come pick up her grandchildren. “Le dio una pela,” she thought—he beat her up. Suliani’s younger sister, Lourdes, grabbed the phone while Sonia ran upstairs to get dressed. She had the presence of mind to ask whether her sister was alive. The officer on the line said, “I can’t give you that information.” That’s the moment she knew the truth. When Sonia came downstairs, they sat down to wait for Lourdes’s then-boyfriend, who would give them a ride. When he arrived, Lourdes broke the news to Sonia: “Suli is not with us anymore.”

It’s been two years since the family lost Suliani Calderón Nieves. In this time, at least 29 women have been fatal victims of intimate partner violence. Yomaira Hernández Martínez, 13, was set on fire by her 19-year-old boyfriend. Moesha Hiraldo Maldonado, 19, was allegedly shot by her partner, but no charges were ever brought. Thyntia M. Cruz Vélez, 27, had her throat slit by her ex-boyfriend. Annette García Arroyo, 31, was stabbed to death by her husband. Yolanda González Muñoz, 49, was shot in the head by her ex-husband in the waiting room of her psychologist’s office. Ana María Morris Colón, 60, was fatally shot by her ex-husband after he called her brother to let him know he intended to kill her.

“Any time they murder a woman, I relive in my heart what was done to my daughter,” Sonia said.

Suliani’s family has been planning to publish all of her poems in a book; they have also talked about potentially creating a foundation in her honor to help victims who are leaving their abusive relationships. Her children, now 12 and 15, live with their dad’s side of the family. “I have to teach my grandchildren this is not love,” Sonia said. “To my granddaughter, I have to teach her if something happens, she needs to seek help and speak up.” But Sonia’s fight has come at a great cost. “I’m going to carry this pain for the rest of my life.”