A judge in Lincoln Parish leased a BMW. Another, from Jefferson Davis Parish, booked a week’s stay in a two-bedroom beachfront condo for five people. A third judge bought an $850 iPhone 12. A fourth had a security system installed in his home.

Defendants who appeared in their courtrooms helped pay for all of it.

This arrangement is perfectly legal under Louisiana state law.

These judges, like most in the country, issue fines and fees. In other states, the resulting revenue is allocated in ways that prevent judges from personally benefiting from the money they extract. But that is not the case in Louisiana. Thanks to a court-funding system with its roots in the Jim Crow era, a portion of the fines and fees issued by Louisiana judges go into a fund that the judges themselves control. Judges have wide discretion to spend these funds on anything related to court operations. Records show that in recent years judges across the state have used these Judicial Expense Funds (JEFs) to pay for expenses ranging from the staff salaries and law library subscriptions to luxury cars and rooms at the Ritz Carlton.

In 2019, a federal court ruled that the use of this system by criminal court judges in New Orleans created a conflict of interest that violates the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The two rulings, Cain v. New Orleans and Caliste v. Cantrell, only applied to the New Orleans court, which reformed their system in response. But the unconstitutional practice they identified persists in nearly every other district court in the state.

The Louisiana Legislature knows it is unconstitutional — in fact, a legislative commission spent years preparing a report with a large section devoted to the constitutional issues raised in those rulings. The judiciary knows it is unconstitutional, too. Officials from the Louisiana Supreme Court led a workshop on the issue and a spokesperson for the court noted that judges were “directed to completely forego the assessment of any fees that are to be explicitly paid ‘to the JEF.’”

And yet years later, state law remains unchanged. Judges face little oversight as they continue to lease cars, pay their cell phone bills, claim mileage reimbursements and collect per diem expenses using money they have taken from the people to whom they are sworn to deliver justice.

Nearly all of Louisiana’s district courts fund themselves through a combination of fines, fees, state grants and local government allocations. WWNO, WRKF and Type Investigations reviewed thousands of pages of audit reports, receipts, financial disclosures and reimbursement requests from dozens of district courts involving hundreds of judges. Our yearlong investigation found that fines and fees charged to criminal defendants were the primary revenue source for about a quarter of the state’s judicial expense funds in 2021 and 2022. Some courts derived over 90% of expense fund revenue from criminal fines and fees and the vast majority collected at least $30,000.

Our investigation — made possible by a new law that requires courts to make standardized financial disclosures about fines and fees revenue — is the first to offer a comprehensive look into how district judges across Louisiana collect and spend these funds.

Altogether, criminal fines and fees poured over $6 million into district court judicial expense funds in 2021 (the first year for which comprehensive data was collected under the new reporting requirements) and over $7 million in 2022. The bulk of these funds were used to pay for staff salaries, office equipment and other court operational costs.

Judges also used a substantial portion of those funds on themselves. Most of the state’s roughly 200 district court judges, for instance, used their expense funds to reimburse themselves for “travel and support” costs that sometimes blurred the line between the personal and the professional. In total, that travel and support spending amounted to about $1.3 million each year.

There are certain limits on travel, vehicle, lodging and per diem meal expenses set by the Louisiana Supreme Court. In the vast majority of records reviewed for this story, judges were in compliance with those limits.

But even the more run-of-the-mill expenses pose a clear conflict of interest, says Micah West, a senior attorney at Southern Poverty Law Center who helped bring a successful lawsuit challenging Louisiana’s system for judicial expense funding.

“They [judges] are only just supposed to make decisions based on the facts and circumstances in your case,” he explained. “But in Louisiana that is not really possible because the court depends on fines and costs to pay for staff salaries, utilities, postage, building maintenance and repairs, transcripts, insurance — basically all the operating expenses of the court. And that is giving judges this incentive to set high bond, to convict you, to impose the maximum fine and costs, to threaten to jail you if you don’t pay.”

When paying up is the only way out

Vermondio Colquitt has spent most of his life in the small town of Haynesville, Louisiana, just south of the Arkansas border. He was a tailback and cornerback on his high school football team, which he helped lead to four state championships in the 1990s. Football is important in Haynesville, where the population has been shrinking for decades and job opportunities have become scarce. Over a quarter of parish residents live beneath the poverty line.

Colquitt’s girlfriend, Jessica Vosburg, says he had to work hard to make ends meet. He trimmed trees and repaired chainsaws for his neighbors, she says, and she helped him field calls and schedule the jobs.

For about a year, after his prior home burned down, Colquitt was staying in a house whose owner he says had asked him to watch the place while she was away.

One day, the police showed up and questioned him. They were investigating the theft of some lawn equipment from a local school, according to Vermondio’s public defender, Allen Haynes.

They searched the house and allegedly found a gun and a small amount of drugs inside. Colquitt still doesn’t know if the gun they found was his, but told officers he owned one, that it was broken and that he had purchased it legally after passing the required background checks.

Police arrested him and put him in a jail cell last May. He was charged with possession of schedule II narcotics and possession of a gun in the presence of illegal substances. Judge Walter May in the 2nd Judicial District set his bond at $251,000.

A wealthier man could have paid to walk free. As of late January, Colquitt was still in the Claiborne Parish Detention Center awaiting trial — more than eight months after his arrest.

He said being in jail and unable to work has had serious consequences. “I got a mother that’s sick. I got a grandpa that’s sick,” he explained. “People depending on me. I can’t do nothing, you know?”

Since very few people can afford to pay their full bail amount in cash, many pay a premium to private bail bonds agents, who then put up the full amount. Nearly every judicial expense fund in Louisiana gets a cut of those premiums.

State law requires that bail bonds companies pay fees that are calculated as a percentage of every premium, with judicial expense funds receiving about a quarter of those fees. In Colquitt’s case, he would have had to come up with over $30,000 to pay the premium on his bond — an amount equal to the median annual household income in Claiborne Parish, where he lives.

Even if a district attorney later dropped the charges, he would never get that money back. The bail bonds company would keep most of it, paying a fee of about $150 into the court’s judicial expense fund. The DA, sheriff and public defenders offices would each get a cut too.

In the 2021 fiscal year, bond fees poured about $35,000 into the 2nd Judicial District’s judicial expense fund. The next year, those fees generated over $55,000 that the judges could use for their expenses.

Because he is unable to post bail, Colquitt, who has not been convicted of any crime, will continue to sit in jail as he awaits his trial. It is a situation in which many Louisianans find themselves. The state has the nation’s highest pretrial incarceration rate, which the ACLU estimates is more than three times the national average.

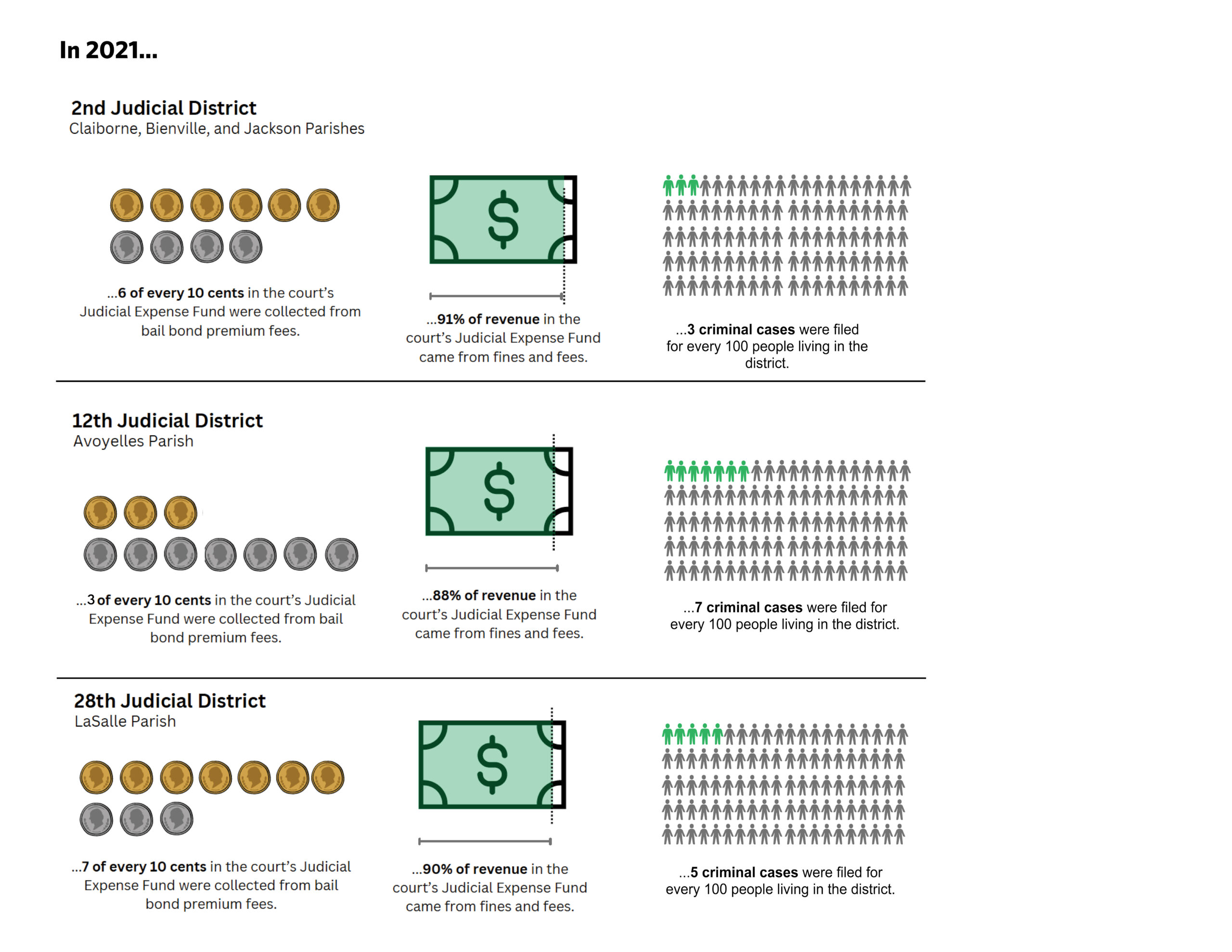

The problem is particularly bad in the 2nd Judicial District, which covers Claiborne, Bienville and Jackson parishes in the northwest corner of the state. A study by the Vera Institute for Justice found that in 2021, one person was incarcerated pretrial for every hundred residents of Claiborne Parish. The district’s judges collected 91% of their expense fund’s revenue through fines and fees that year, with over six in every ten cents in the fund coming from bail bond fees.

Data pertaining to judicial expense funds was obtained from the Louisiana Supreme Court, which collected it per Act 116 reporting requirements. District population data is calculated from U.S. census parish population data. Criminal case filing data is from the Louisiana Supreme Court’s 2021 Annual Report. Image: Garrett Hazelwood

The judges of the 2nd district court also report unusually high expenses. Judge Glenn Fallin expensed over $20,000 in fiscal year 2021, making him one of the highest spending judges in the state.

According to reimbursement requests he filed with the court, his expenses included $1,332 in mileage for driving over 2,300 miles on a pair of back-to-back trips he made from Bienville Parish to Destin, Florida for legal conferences and events. That year, he drove a vehicle that he leased with help from a $600 per month subsidy he was paid from the Judicial Expense Fund.

He also expensed $1,652 for his per diem allowance during those two trips. In each case, he was reimbursed before leaving on the trips. The court does not have any receipts on file to account for his actual fuel or meal expenses. According to a court audit report filed with the Louisiana Legislative Auditor, his total per diem expenses in 2021 were $4,482.

Also in the 2nd Judicial District, Judge Walter May drew more than $12,000 from the Judicial Expense Fund within his first seven months in office — more than many district judges spend in a full year. His spending included $600 per month for his vehicle lease and fuel and nearly $1,500 on cell phone-related costs.

Judge May told WWNO, WRKF and Type he believes that the 2nd district is one of the largest in the state, and that he lives in a different parish than the one where he typically presides, necessitating long commutes. He leases a 2020 Ford Fusion and wrote that a good cell phone is necessary for performing his duties, which often require him to remotely set bond, sign warrants and hold 72-hour hearings.

Judge Fallin did not respond to a request for comment, nor did Judge Rick Warren, who also presides in the 2nd district.

Cash for convictions

In addition to the bail fees, judicial expense funds also receive revenue from a fee charged to anyone who is convicted or pleads guilty to a crime. The judges of each district court are authorized to determine the fee amount up to a certain limit. Depending on the court, the fee typically ranges from $5 to $25. But for those convicted for felonies, the costs can be even steeper — up to $500 in at least one district.

In a 2018 speech to the legislature, former Louisiana Supreme Court Chief Justice Bernette Joshua Johnson called for reform and pointed out the perverse incentives the funding scheme creates.

“Innocence, though presumed by our system, is currently bad for our bottom line,” she said. “Would you have faith in the system if you knew that every single actor in the criminal justice system — including the judge and your court-appointed lawyer — relied upon a steady stream of guilty pleas and verdicts to fund their offices? Would you doubt your ability to get justice?”

The Orleans Parish criminal district courthouse in New Orleans, LA on Jan. 29, 2024. The federal Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in 2019 that the use of a judicial expense fund by district judges in Orleans Parish was unconstitutional. The inscription on the facade of the building reads, “The impartial administration of justice is the foundation of liberty.” Image: Garrett Hazelwood

For anyone on the receiving end of those verdicts, court costs and conviction fees can amount to an impossible burden, says Gabrielle Perry, executive director of the nonprofit Thurman Perry Foundation, which supports women impacted by incarceration.

Perry was arrested in 2014 in Baton Rouge on charges of payroll fraud from a work-study program while she was a student at Louisiana State University. She paid bail and was released from jail. “That’s when the real punishment started for me,” she said.

Because she had an arrest on her record, “I just couldn’t get anyone to hire me,” she said. “I couldn’t find a place to live. I didn’t have any money. And court fees have to be paid.”

She said she was forced to dedicate the bulk of what little money she could make to paying off her restitution payments and about $1,500 in court costs, and as a result became unhoused for almost a year.

“I had a bunch of payday loans, just trying to literally get to the next day,” she recalled. “I used to have panic attacks […] knowing when my next court date was coming up, because I was like, ‘Okay, well, what do I need to pay?’”

Paying for the ‘proper administration’ of their courts

While some, like Perry, are forced to choose between paying court debt or paying rent, judges in Louisiana are spending money taken from defendants to book stays in luxury hotels.

Judge Steve Gunnell is the only judge in the 31st judicial district court. That means he has sole control over the court’s judicial expense fund. His annual expense claims in recent years rank among the highest of any district judge in the state, reaching nearly $20,000 in 2018, according to the court’s annual audit report.

In at least three of the past five years, Gunnell has attended an annual weeklong judicial conference in Florida, using the maximum amount allowed for lodging from his Judicial Expense Fund each year to book a two-bedroom beachfront condo for the week.

During one of those trips, receipts show the condo was booked for four adults and one child. In 2021, he also expensed two nights and valet parking at the Ritz Carlton in New Orleans while attending a legal seminar at the hotel. That same year, he spent about $1,700 in per diem meal expenses and paid nearly $2,000 for his cell phone costs.

Through the court’s judicial administrator, Gunnell declined to comment on the expenses.

These expenses were all perfectly within the letter of the law. In fact, Louisiana lawmakers have given judges the power to spend Judicial Expense Funds however they see fit.

Per state law, district judges can use these funds for “any purpose or purposes connected with, incidental to, or related to the proper administration or function of [their] court.” With this broad mandate as their guide, the judges of each court must decide as a group how to administer the funds. While some courts have a dozen or more judges to make those decisions, nearly 20% of Louisiana’s 42 district courts are administered by a single judge, who has sole discretion over how money from the court’s Judicial Expense Fund is spent.

Each district court has its own rules and systems. In some courts, judges set bail and control the revenue. In others, a commissioner sets bail but does not have control of the judicial expense funds. Some courts receive the bulk of their judicial expense funding from local government allocations, while others are mostly funded through fines and fees. The fines and fees themselves vary widely depending on local rules.

As a result of this decentralized system, “you can commit the same crime in two different parishes, and it will cost you five times as much in Ouachita Parish as it will in Orleans,” according to Vanessa Spinazola, former executive director of the Justice and Accountability Center of Louisiana.

Because the courts generate much of their own funding through fines and fees, they require less support from parish and state budgets. That situation “insulates courts from political accountability,” says West. “They don’t have to make their case for funding or explain how they spend their money. They operate like an independent fiefdom.”

The Ritz Carlton hotel in New Orleans on Dec. 8, 2023. While attending a legal seminar there in 2021, Judge Steve Gunnell, who presides in Jefferson Davis Parish, used money from his court’s judicial expense fund to pay for two nights and valet parking at the 5-star hotel. Image: Garrett Hazelwood

The limits that do exist on judicial expenses are far more lax than the rules for all other state officials in the executive and legislative branches. Judges in Louisiana may spend nearly three times the amount that other officials are allowed for lodging during an annual conference in Destin, Florida, for example. Their meal per diem cap is about twice the limit other officials must follow and among the highest allowed for any judges in the country. Judges in multiparish districts are also among the only Louisiana officials able to claim cash reimbursements with public funds for leasing vehicles under their own names — as opposed to the court leasing those vehicles and making them available for judge’s official use.

Robert Gunn, a deputy judicial administrator for the LASC, wrote in an email that the expense and travel limits are based on a “standard of reasonableness,” and that comparisons to other branches of government may be inappropriate because judges’ obligations are distinct from those of other officials: They are required to attend continuing legal education courses, their positions are full-time and they can be investigated and removed for unethical conduct.

The amounts and types of expenses judges claim vary dramatically. Some judges spend their maximum vehicle allotment of $7,200 annually, leasing Lexuses or other expensive cars, while others spend far less leasing more affordable vehicles, renting cars on an as-needed basis or claiming reimbursements for fewer payments. In the 6th Judicial District Court — which covers East Carroll, Madison and Tensas Parishes — the court’s two judges charged only $400 in travel and support expenses and claimed no other reimbursements for themselves from their judicial expense fund in the 2021 fiscal year.

During the same period, the three judges of the 3rd Judicial District Court, which covers Lincoln and Union parishes, racked up $26,712 in travel and support expenses, including reimbursements paid to Judge Thomas Rogers of $6,617 to help lease a BMW.

His financial disclosure documents show he owns at least $900,000 in real estate, including seven rental properties in Lincoln Parish. He used over $5,000 from the judicial expense fund between 2019 and 2022 to pay for separate cellular plans for his phone, iPad and Apple Watch.

Rogers noted in a phone interview that he paid for the initial purchases of the iPad and Apple Watch with his own money, that he uses the iPad for legal research and that the watch helps him keep up with phone calls while on the bench.

He also stressed that the funds did not influence his decision making. “You know, I’ll say that I wish there was a different system, but there’s not,” he said. “But it certainly doesn’t affect the way I’ve sentenced criminal defendants.”

One judge’s spending also reached far beyond the courtroom, into his own home. Judge William Bennett of the 12th district, which encompasses Avoyelles Parish, said he used nearly $5,000 from the Judicial Expense Fund to purchase a home security system in 2018. At various points, the system included a unit for recording video from multiple cameras, a panic button, a cell phone app and active monitoring by the security company. Technicians from the company came out to Judge Bennett’s home at least twice in 2021 to service it. The court’s audit report shows Judge Bennett expensed $3,511 for the system’s maintenance and his home internet service that year.

Judge Bennett said he installed the system after receiving credible death threats during a case that attracted national media attention, noting that he purchased it only after consulting and securing approval from the Louisiana Supreme Court. He pointed to an opinion by the attorney general holding that judges could use judicial expense funds for such purchases. He also explained that he will be required to return or purchase the system with his own funds at its depreciated value at the end of his term.

‘I just wanted to get out‘

In a state that in recent years has had the highest poverty rate in the nation, the cycle of debt and incarceration is a trap that can be incredibly difficult to escape.

For Kade Duplechin, the financial incentives built into Louisiana’s judicial system have been upending his life for years.

Duplechin was arrested in 2019 for resisting arrest and simple burglary, a felony charge he was given for trespassing in a scrap yard in Lafayette, near where he says he had been sleeping during a period in which he was unhoused.

He was only accused of taking a few handfuls of nuts and bolts (that he claims he had actually collected from the roadside) and had entered through a gap in the fence without causing any damage, but the crime is defined as unlawful entry “with intent to commit a felony or any theft within.” He was jailed for nearly four months before even being arraigned, then pled not guilty and was returned to jail for another five-and-a-half months while awaiting trial.

After locking him up for almost ten months pretrial, they offered him a choice: either stand trial and risk a 12-year maximum sentence or plead guilty and be released with three years of probation. Duplechin pleaded guilty.

As a 2023 paper in the Harvard Law Review describes, many prosecutors “charge a criminal defendant by overlapping or duplicating offenses and then, after pressure on the defendant looms, agree to reduce the charges in number or in severity in exchange for a guilty plea.” In Louisiana, a guilty plea to any criminal charge results in a conviction fee that — for most district courts — goes directly into the judicial expense fund.

“I just couldn’t take it no more. I just wanted to get out,” Duplechin said. “So I just signed the papers.”

Kade Duplechin was released from jail in late 2023. As of January 2024, he says he is now enrolled in a university, working, and living with family. Image: Courtesy of Kade Duplechin

The judge fined him $750 and ordered him to pay $435.50 in court costs within six months, of which $20 would go into the court’s Judicial Expense Fund. She also ordered him to pay a $250 fee to help support the Acadiana Crime Lab, $100 fee for the Drug Abuse Education and Treatment Fund, $60 a month for his probation supervision fees, and $11 each month for the Sex Offender Registry Technology Fund — though his case hadn’t required lab work and had nothing to do with sex.

He was released in early 2020, just as the COVID pandemic was sweeping the country, and was quickly back to living on the street. Broke, Duplechin says he couldn’t pay his fines or fees.

Often without a cell phone, it was difficult to call his parole officer to check in. A felon, he faced serious barriers to finding work. Without an address, he couldn’t receive mail about his court dates. Without a car, it was a monumental task to get to court anyway.

In July of 2022, he called his parole officer to try to get things sorted out. He told her he had finally gotten a job and found housing, that he was off drugs. When he missed his next court date, the judge issued a warrant.

“When I finally did get on my feet, that’s when I realized I still had this warrant, and I felt like I got clean for nothing. You know…it’s just been one thing after another.”

He was arrested and jailed again in January 2023 for theft of an item worth less than $100, resisting an officer and parole violation. By then he owed $2,970.50 in fines, fees and court costs, plus an additional $2,100 in the monthly supervision fees for his parole.

When he appeared in court again, he was chained at the wrists and ankles, wearing a black-and-white-striped jumpsuit. The chains clinked with each step as he was brought to stand before Judge Marilyn Castle in the Lafayette courthouse.

The parole officer testified that she hadn’t heard from him except the one time, and that he hadn’t paid his fees. His public defender informed Judge Castle that he had been unhoused. Judge Castle sent him back to jail for another 7 months, to be followed by another year of probation.

Judges oppose reforms

Duplechin is among thousands of Louisianans for whom the heavy burden of court-ordered debt plays a role in leading them to reoffend and wind up back behind bars. It is a problem that the Legislature has taken steps to address in recent years. But efforts to fix it have been slow moving and limited in scope.

Lawmakers passed a landmark criminal justice reform package in 2017 known as the Justice Reinvestment Act. That reform package included Act 260, which was aimed at preventing courts from collecting fines and fees that would “cause substantial financial hardship to the defendant or his dependents.” After its passage, implementation of the law was delayed for five full years amid concerns that it could bankrupt courts across the state. But in 2022, it finally went into effect. Judges are now required to waive financial penalties, offer manageable payment plans, or order non-monetary alternatives such as community service to those who they deem are unable to pay.

Yet most of the new financial hardship allowances only apply to people convicted of felonies. And most of the ability-to-pay determinations are made by judges who have conflicting incentives to collect money for their Judicial Expense Funds and ensure that their courts are sufficiently funded. So while judges are supposed to start waiving financial penalties for a subset of the poorest defendants, the state’s court system still depends upon a vast patchwork of fines and fees.

“Courts are fearful of losing those funds,” said West, the attorney with Southern Poverty Law Center. “There is just not the political will and trust that if we move away from this reliance on court costs and fines, that there will be consistent funding from the Legislature.”

In a phone interview, Judge Bennett of Avoyelles Parish pointed out that the Legislature created the fee-based system that judges use — and that it’s their responsibility to fix it. “The law mandates it,” he said. “So if it is a conflict, change the law and we’ve got to find another source of funding.”

The courts are not alone in their reliance on fines and fees. Crime labs, district attorneys, sheriffs, public defenders and many other criminal justice entities across the state also depend on court-ordered fines and fees to keep their operations running.

The Legislature created the Louisiana Commission on Justice System Funding in 2019 to study the state’s ecosystem of criminal fines and fees and propose alternative ways of funding the courts. The commission was composed of a variety of stakeholders, including judges, a parole officer, a district attorney, a public defender, and prison reform advocates. After the decisions in Cain v. New Orleans and Caliste v. Cantrell, the commission expanded its focus to also assess what statewide changes were necessary to avoid the unconstitutional conflicts of interest related to judicial expense funds that were highlighted by those federal rulings.

“Maybe we shouldn’t be writing a blank check for the current size of the system.”

The commission soon found that each of the approximately 250 courts in Louisiana had its own set of fines and fees and kept records according to its own system of bookkeeping, so that it was nearly impossible to know how much money was being collected by courts statewide or how much funding would need to be replaced if certain fines and fees were eliminated. Though the commission recommended standardizing financial reporting requirements, the process to implement them is slow and complex. Diane Allison, director of local government services at the Louisiana Legislative Auditor, said that just four people in the LLA were working on it.

Gunn, the LASC spokesperson, told WWNO, WRKF and Type that after a “tremulous start,” the data collection process was improving and would allow the court to “better assess the ‘price of justice.’”

The LASC hopes to use the new data to calculate how much additional funding from the state is needed to replace fines and fees, Gunn wrote. But not everyone believes that’s the correct way to solve the problem.

Former Justice and Accountability Center of Louisiana Executive Director Vanessa Spinazola, who was a member of the commission, said that many of their discussions focused on finding “a one-to-one replacement for whatever this is going to cost,” rather than considering ways to shrink the system and prevent people from going through the criminal process in the first place.

“Where there wasn’t a lot of conversation on the commission is the question of like, well maybe the system shouldn’t be as big as it is. Maybe we shouldn’t be writing a blank check for the current size of the system,” Spinazola said. “But they just didn’t want to talk about that.”

The entrance of the Louisiana Supreme Court building in New Orleans’ French Quarter on Jan. 29, 2024. Six of seven Louisiana Supreme Court justices recently signed a letter in opposition to a proposed bill that would have put tighter limits on judges’ expense spending by forcing judges to follow the federal per diem rates that other state officials are required to abide by. Image: Garrett Hazelwood

The commission dissolved without recommending any other legislative reforms to reduce financial burdens on defendants or fix the conflicts of interest. In their final report, the commission didn’t recommend eliminating even a single fee.

West suggests one possible reason why: “A lot of members of the commission depended on the fines and costs to fund their agencies.”

In fact, the commission’s membership structure was changed in its second year to add two bail industry representatives and a member of the Crime Victims Reparations Board, meaning that over half the commission’s members were representatives of groups that receive funding from court fines and fees.

Given the lack of legislative action, the Louisiana Supreme Court justices sent a letter to the governor in October expressing their concern and asking for help. “The issue of ensuring proper, constitutional funding for our courts is something that is critical for the future of our state,” they wrote.

There are many potential reforms that experts say could help shrink Louisiana’s judiciary. Loyola University of New Orleans Law Prof. Will Snowden suggests, for example, that there should be a much higher bar for arrests. Judges currently issue arrest warrants based solely on accusations, allowing police to arrest people with little to no investigation nor evidence. District Attorneys could also implement a screening process to prevent people from being held in jail on charges that the DA will later decline to prosecute.

The legislature has also considered placing tighter limits on the expense spending that judges are allowed, which would ultimately reduce the judiciary’s operating costs. A bill proposed by Republican Rep. Jerome Zeringue of Terrebonne Parish would force judges to comply with the same U.S. General Services Administration spending caps for meals, lodging and other incidental expenses that all other elected officials in Louisiana are required to abide by.

But the bill faces an uphill battle, as six of the seven state Supreme Court justices have come out against it, writing a letter in opposition that they distributed to lawmakers in which they claimed the limits would be punitive to judges and neither reduce the judicial budget nor save taxpayers money. Some lawmakers are also hesitant to get behind judicial reforms because they are also attorneys who must argue cases before the judges whose spending they are being asked to reign in.

Rep. Zeringue is also leading another, potentially more consequential, effort to reform the judiciary. As chair of the Judicial Structure Taskforce, he is overseeing a joint effort by judges and lawmakers to study the workload of the courts and restructure the judiciary to make it more efficient and better aligned with the significant population changes and shifting caseloads that have occurred over the past several decades. The changes being considered include reapportioning the number of judgeships.

As one of the first steps in that process, the task force contracted the National Center for State Courts to conduct an independent study of the workload of district and appellate courts throughout the state. The center frequently performs such studies. Yet taskforce members say they have met with tremendous pushback from the judiciary in Louisiana, with judges refusing to attend task force meetings or report certain data. Some have filed letters in opposition.

The possibility that the NCSC study will recommend the shrinking of Louisiana’s court system, potentially by eliminating numerous judgeships, looms large over the fight. That outcome would be a reversal of the growth of the judiciary over recent decades, even as the number of cases it handles has declined, according to data compiled by the Louisiana Supreme Court.

Whatever the solution, it will take an enormous effort to shake the status quo.

“It’s certainly something worthwhile to try to make simpler and maybe less burdensome on some of the criminal defendants,” said Judge Rogers of the 3rd district.

“I don’t think anybody would argue that point. But if not them, if not the criminal defendants, then who will bear that cost?”

This story was produced with support from the Fund for Constitutional Government.