Brandon Russell’s letters were detailed: first a how-to diagram for building a functional explosive device. Then instructions for dropping propaganda leaflets by air. In another, an ominous warning: “As soon as I get out, I will go right back to fight for my White Race and my America!”

He was already incarcerated when he wrote those letters from the Pinellas County Jail in Clearwater, Florida, hoping they would land in the hands of a fellow neo-Nazi. His 2018 conviction for possession of explosive materials had done nothing to dissuade his neo-accelerationist dreams: He wanted the social order to collapse, giving way to ethnic cleansing and the eventual rise of a National Socialist order. But the letters were intercepted and turned over to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Prosecutors cited Russell’s jailhouse correspondence as the basis for a heavier sentence than the five years he ultimately received.

“Russell is not someone whose arrest and incarceration has caused him to reflect on his conduct or feel remorse. His conduct in this case posed a grave danger to human life, and he has shown that he will continue to be dangerous once released from incarceration,” the feds wrote in a January 2018 motion. And over the course of Russell’s five-year imprisonment, he continued to radicalize.

The Atomwaffen Division (from the German word for atomic weapons), which Russell founded with his friend Devon Arthurs in 2015, was still embryonic in mid-2017, with a handful of cells around the United States. At the time, the neofascist youth revival known colloquially as the alt-right was ascendant, spewing hatred freely online and clashing with anti-fascist counterprotesters at rallies across the country. The arrest and imprisonment of the Atomwaffen Division’s founders did not kneecap the group’s rise. To the contrary, it helped fuel its growth.

Russell had rented an apartment in Tampa, where he lived with three other AWD members: Arthurs, Andrew Oneschuk, and Jeremy Himmelman—the latter two young fascists who’d moved south from Massachusetts into an apartment filled with firearms, fascist flags, and memorabilia, such as a framed photograph of Timothy McVeigh. In their spare time the young men would hike, go on Airsoft shooting missions, and push recruitment. Russell had the group’s insignia inked on his right shoulder.

On May 19, 2017, Arthurs murdered Himmelman and Oneschuk with an assault rifle in a fit of rage. When police searched the apartment, they discovered the arsenal, reams of propaganda, and a cooler full of highly unstable homemade explosives belonging to Russell. Arthurs was arrested immediately; Russell was arrested two days later. Local law enforcement had allowed Russell to leave the scene of Arthurs’s massacre despite the presence of homemade explosives. (In 2023, Arthurs pleaded guilty to two counts of murder and three counts of kidnapping and was sentenced to 45 years in state prison.)

When Russell was first charged with explosives offenses in 2017, a federal judge released him on bond, claiming there was no “clear and convincing evidence” that he posed a danger to the public. Russell was in possession of rifles, ammunition, homemade body armor, binoculars, and a skull mask when he was arrested. During his interrogation, Arthurs had told police that Russell wanted to attack a nuclear plant south of Miami, prompting a judge to revoke Russell’s bail before his trial.

Russell had been an intelligent but immature kid—one elementary school classmate described him to Rolling Stone as a “radioactive boy scout”—who grew up in ease and affluence, but the arrest threw him into the cold reality of American carceral institutions for the first time.

Following Russell’s conviction and against the backdrop of a resurgent white supremacist movement in America that rode the coattails of Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential victory, Atomwaffen grew into one of the extreme right’s most notorious organizations. It posted provocative propaganda videos, flyered campuses, and published a set of obscure neo-Nazi texts that are now central to a particularly violent segment of the global extreme right. The group’s flecktarn-camouflaged fatigues and skull-mask balaclavas have become staples of extreme right-wing imagery. Atomwaffen’s core text, Siege, which promotes murder, infrastructure destruction, and dispersed guerrilla tactics meant to destabilize society, has helped define the concept of accelerationism that is now common currency in the extreme right.

After the deadly events in Charlottesville, Virginia, Southern California cadre member Samuel Woodward murdered Blaze Bernstein, a gay Jewish student, in what authorities called a hate crime (he was convicted after a three-month trial in July). Nicholas Giampa, a teenage affiliate of Atomwaffen, killed his girlfriend’s mother and stepfather after they forbade him from dating their daughter because he’d mowed a giant swastika into the lawn of their subdivision in Virginia.

Demonstrators in Charlottesville. Image: Albin Lohr-Jones/SIPA USA/AP

Yet Russell’s probation conditions didn’t restrict his internet usage or ability to associate with extremists. Even when photographs of Russell’s posts in the company of AWD comrades and extremist remarks on a now defunct Twitter account were sent to his federal probation officer by concerned extremism researchers, law enforcement did not revoke his supervised release. “He could’ve restarted the Atomwaffen Division and not been in violation of his agreement,” says Pete Simi, a sociology professor at Chapman University who has studied far-right extremism for decades.

“People always complain about prison being the worst thing that could happen to their lives. But honestly, I met some of my best friends in prison, had some great times and great laughs, and was shown a ton of love and support from those who cared about me on the outside,” Russell wrote in an October 2021 post with a sketch and photograph of himself at the federal prison in Terre Haute, Indiana, featuring his head framed by a Black Sun with the caption “The Most Dangerous Man in America.”

America’s young neofascists like Russell are at an inflection point: Many of the movement’s figureheads are heading into their second or third stints in prison for increasingly serious crimes. Other prominent right-wing extremists convicted and sentenced in the past decade or so are either nearing the end of their prison terms or have been released back into society. Like countless extremists before them, from developing-nation independence heroes to the Maoist student guerrillas of 1960s Europe to jihadis, prison is now functioning as a finishing school for the would-be progenitors of an American reich.

Locking up extremists for their crimes is necessary, but by no stretch of the imagination does it solve the underlying problems. Following his conviction for the failed 1923 coup d’etat known as the Beer Hall Putsch, Adolph Hitler honed his myth while imprisoned for high treason, authoring Mein Kampf, vastly expanding his notoriety and continuing his ascent to power.

The Terre Haute, Indiana, federal prison complex where Atomwaffen Division founder Brandon Russell was incarcerated. Image: AP Photo/Michael Conroy, File

The stories of Brandon Russell; Robert Rundo, a former gang member turned Nazi street fighter from Queens, New York; and Jacob Kaderli, a fascist from suburban Georgia, all exemplify how the realities of prison further radicalize America’s extreme right wing.

We are almost a decade into the neofascist revival, and there are no signs of its momentum abating. Once-fringe concepts like the Great Replacement are now echoed in Congress, and January 6 demonstrated the potential of street-fighting extremists to serve as instruments of erstwhile dictators. The far right—and this is a youth-led movement—has succeeded in the creation of an organic neofascist sub/counterculture. It has adopted elements of older National Socialist culture and updated it—Black Suns, the balaclava-and-tracksuit aesthetic of Balkan genocidaire militias and the Irish Republican Army, The Turner Diaries, the half skull mask, McVeigh—to build its own virulent, seductive world.

On the spectrum of the American far right, the further out you go, there’s less wanting a “friendlier Nazi Germany” and more mass exterminations, Charles Manson–style helter-skelter, and forging a Fourth Reich. Violence is paramount. Subversion is key. And the young men who drive the propagation of neofascist sub/counterculture are wholly committed to the cause. While women occupy an essential place, the world of the modern-day brownshirts is almost exclusively male. To them, the January 6 invasion of the Capitol was mild: They’ve assaulted ideological opponents at rallies and plotted to murder anti-fascist families, disable the power grid, and shoot up a gun-rights rally. They hew to a time-honored tradition of “leaderless resistance,” and they’ve succeeded in emulating it to a degree, with copycat massacres in Pittsburgh, El Paso, Buffalo, and elsewhere, by perpetrators lionized as “saints.” These overtly accelerationist attacks like the Buffalo massacre are aimed at “soft” targets, not heads of state, and seek to destabilize the social order by ramping up political and racial tensions.

According to a February 2023 Government Accountability Office report, the FBI tallied 9,049 cases related to domestic terrorism in 2021, up from 5,557 in 2020, 4,092 such cases in 2019, and 3,714 in 2018. In 2017, the year of Unite the Right, there were 1,890 domestic-terrorism-related cases, on par with the preceding four years, during which time the FBI was largely focused on Muslim jihadis. (A spokesperson for the Department of Justice declined to comment for this story.) “White supremacist ideas, symbols, and groups are widely circulating, including in the White House during the last administration and Congress,” says Simi. “From that to the more radical manifestations of that ideology, the neofascist aspects and the violence, it’s not that far of a bridge to cross.”

Now the architects of this subculture are heading to prison for their first, second, or third stints in custody for violent offenses. And alongside them, there are hundreds of January 6 participants on their way to or in the Bureau of Prisons system: As of August 2024, the Justice Department has charged more than 1,400 people with criminal offenses stemming from the insurrection and more than 900 defendants have pleaded guilty.

The sentencing patterns to date of the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys leaders convicted of seditious conspiracy do not inspire confidence: All have been sent to medium-security facilities, including federal prisons like Cumberland, Manchester, Coleman, and Talladega. The “Patriot Wing”—the name alleged insurrectionists in the Washington, DC, jail gave to their housing unit—is known to have fostered solidarity among January 6 defendants. So the role of correctional systems in tracking and responsibly housing extreme-right inmates is crucial.

Yet there currently is no deradicalization or intervention curriculum for federal prisoners with domestic terrorism convictions, either inside prisons or upon their release back into society. By contrast, Germany’s state governments and its domestic intelligence agency spend millions of euros annually on anti-extremism education and deradicalization efforts. The Federal Bureau of Prisons did not return requests for comment.

The sentencing patters to date of the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys leaders convicted of seditious conspiracy do not inspire confidence.

“Replacement theory is being discussed not only on national TV, it’s also being discussed at bars, pool halls, and dinner tables,” says Brian Levin, a criminologist and professor emeritus at California State University–San Bernardino. “We’re not only failing to equip people to critically understand the roots of previous societal divisions from yesteryear that impact us today; we’re failing to address how these prejudices are amplified.”

“The danger is not only from these ideologues forming their own militant organizations bent on violence,” he adds, “but their influential role in a more broad cultural context with those who aren’t quite Nazis.”

Along with societal factors, each extremist’s background determines how receptive they’ll be to counterprogramming, according to a foundational 1993 study by Jack Levin and Jack McDevitt, which groups far-right-wing adherents into three archetypes. There are thrill offenders, by and large young men who might fall into the category of “edgelords,” who act on peer validation, with the least degree of ideological indoctrination. Then there are defensive reactive offenders, who form their worldview from conflict with other racial groups or a loss of status; the personal nature of their animus can be countered with lived experiences. Mission-driven offenders, which include some true sociopaths, are by far the hardest people to reach. “Their composition changes over time,” says Levin. “Hardcore racist skinhead offenders, Klansmen, Atomwaffen Division.”

After his conviction in 2018, Russell was sent to a low-security penitentiary in Atlanta. Within six months he participated in a propaganda video with his comrades on the outside where he reaffirmed his commitment to millenarian neofascism and threatened three former members suspected of betraying Atomwaffen. After the video’s release and subsequent media coverage, the Bureau of Prisons relocated Russell to a secretive isolation unit in Terre Haute reserved for extremist prisoners in a mothballed section of that facility’s death row.

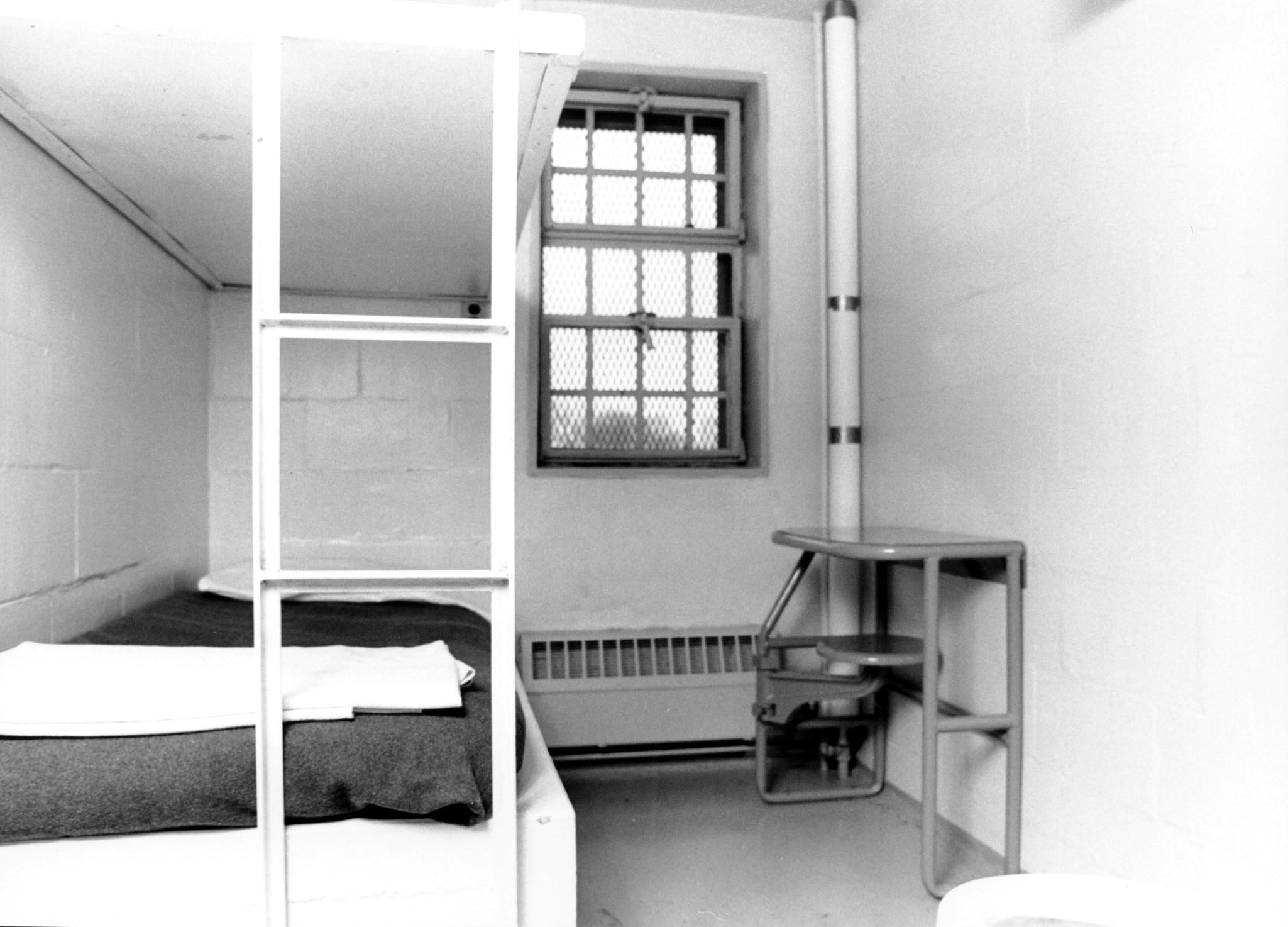

A Special Confinement Unit cell in the Terre Haute penitentiary. Image: UPI

Created quietly in 2006 by the Bush administration to house “dangerous terrorists” during the post-9/11 era, Terre Haute’s Communications Management Unit, known as Gitmo North, is one of two such facilities in the country (the other is in Marion, Illinois). In their early years, the CMUs were overwhelmingly filled with Muslim inmates sentenced on terrorism-related charges. Occasionally prison officials would assign inmates from a hard-left tendency as what a former inmate described as a “balancer” to vary the unit’s ethnic and racial composition, along with hard-core neo-Nazi terrorists like Richard Scutari of the Order; Matthew Hale, who schemed to assassinate a federal judge; and Dennis Mahon, part of the Aryan Republican Army bank robbery crew that had ties to McVeigh.

The CMU’s inmate population, which increased by 140 percent from 2007 to 2022, faces heavy restrictions, including monitoring of all correspondence and a restrictive visitation policy. Letters, emails, and phone calls to and from prisoners are documented in weekly intelligence reports, some of which have sporadically trickled out into public view. Analysts in the Bureau of Prisons’ counterterrorism unit in Martinsburg, West Virginia, scrutinize the communications and compile weekly intelligence summaries. (The BOP denied Freedom of Information Act requests for documents about correspondence between CMU inmates and the outside world during Russell’s term, citing inmate privacy.)

Andy Stepanian, an animal rights activist imprisoned for a controversial conviction involving a lab targeted by saboteurs, served almost six months at the Marion CMU in the late 2000s. Pointing to specialized “terrorism” units in France and the UK where inmates have come out more radicalized and gone on to commit attacks, Stepanian claims that CMUs have a similar impact. “Prisons are a petri dish for this kind of stuff,” he says. Confining inmates based on ideology, Stepanian observes, lumps people with lesser offenses and weaker beliefs in with genuine zealots, and often “they came out with a more radicalized ideology.”

“For these alt-right guys,” Stepanian says, “it is going to be like a finishing school for them, if they can make it through.”

Confining inmates based on supposed ideology lumps those with lesser offenses in with genuine zealots— meaning those with weaker beliefs can come out radicalized.

According to a source with knowledge, at Terre Haute Russell became acquainted with Walter Bond, a Salt Lake City vegan convicted of burning down businesses in Colorado and Utah that sold animal products. Bond, who claimed the arsons under the alias ALF Lone Wolf, was sent to the Terre Haute unit in 2018 after serving a three-year stint in Marion. He showed no remorse at his 2011 sentencing hearing and signed his prison communiqués “Walter Bond, ALF-POW,” indicating he viewed himself as a prisoner of war. Bond’s ideological commitment was emblazoned on his body in the form of crossed wrenches (the insignia of 1980s punk band Earth Crisis, which was closely associated with the Earth First! movement and the Animal Liberation Front) and “vegan” tattoos on his neck.

Bond’s influence on Russell was immediately apparent on his release in August 2021. The Atomwaffen founder adopted the alias Raccoon online, littered his Twitter feed with animal rights–themed posts, and posted a photograph of himself at a Florida bar wearing an ALF T-shirt. Bond also drifted to the right, sending Third Reich–era vegan propaganda to his pen pals and earning a disavowal from former supporters for his “eco-fascist trajectory.” After leaving prison, Bond met with Ryan Hatfield, an Atomwaffen comrade of Russell’s from Denver, before being reincarcerated last year for nine months over a probation violation.

During Russell’s incarceration, the Atomwaffen Division moved from the fringes of the far right to the mainstream. Copycat groups sprung up throughout North America, Europe, and Australia, even after a multistate FBI operation in February 2020 rolled up the remainder of AWD’s leadership. “When we were doing the Base and Atomwaffen, accelerationists were kind of ‘cringe,’ ” says one veteran FBI agent. “Two years after that, 90 percent of all white nationalists online were accelerationists, which was scary.”

Russell posts his prison tattoo of AWD’s logo. Image: Twitter

Upon returning to the civilian world, Russell dove right back into his extreme-right milieu. Instead of Odin, his old handle, Russell changed his aliases up, shuffling between Raccoon, Homunculus, and Ouroboros to conceal his identity. He published his prison writing on a website run by AWD’s remnants, along with post-release essays inspired by Unabomber Ted Kaczynski. Russell was also prolific on Telegram, circulating maps of energy and rail infrastructure and sharing the personal information of government employees.

Meanwhile he became active in the Terrorgram Collective, a loose-knit international network that creates and disseminates noxious neo-Nazi media with the dual purpose of “black-pilling” young people and inspiring lone-wolf attacks. The organization’s four major publications are dense, slickly produced neofascist tracts geared toward radicalizing youth with Atomwaffen, Green Anarchist, anti-police, and Great Replacement ideology, blended with unvarnished Hitler worship.

Rather than simple manifestos, Terrorgram publications included bomb-making instructions and tactical advice on how to disrupt power lines and poison water distribution systems. The Terrorgram publications also feature lurid references to neo-Nazi mass murderers like McVeigh and Norwegian killer Anders Breivik; one page includes a photo of every one of Breivik’s 77 victims. The “saints” and their “high scores” fit squarely within the white nationalist tradition back to Louis Beam’s Essays of a Klansman, which established a points system for “Aryan Warriorhood” based on criminal acts (including murder) in furtherance of the movement. In early September, federal prosecutors charged Dallas Humber and Matthew Allison with a 15-count indictment for soliciting hate crimes, soliciting the murder of federal officials, and conspiring to provide material support to terrorists.

Russell’s term in the CMU was notable for another reason: Sarah Clendaniel, a Maryland woman with white nationalist leanings serving state time for armed robbery, struck up a correspondence with him. The two began a romantic relationship, which continued when they were released. Court documents show Russell and Clendaniel recruited potential coconspirators via extremist Telegram channels, leading to their arrest last February for conspiring to destroy power substations around Baltimore and sow chaos with rolling blackouts. In addition to the Baltimore plot, Russell was trying to recruit people for “IRL activism” in Florida (a euphemism that can include sabotage and property destruction) and frequently promoted news about a decade-high wave of nationwide power grid attacks in late 2022 that preoccupied law enforcement.

Sarah Clendaniel, who was romantically linked to Russell. Image: Department of Justice.

Russell’s trial is set for mid-November. His attorneys have kicked up dust by enlisting the American Civil Liberties Union to disclose what they claim is evidence of warrantless surveillance by American intelligence agencies that led to Russell’s arrest. Great Britain formally banned the accelerationist group last spring, which provided greater authority for surveillance for the UK and its allies. Clendaniel pleaded guilty to her charges earlier this year and may testify against her former paramour.

Russell faces a lengthy sentence and could be returned to the CMU at Terre Haute or Marion if not the “supermax” federal penitentiary in Florence, Colorado, alongside America’s highest-profile terrorism convicts.

Jacob Kaderli, like Russell, was a son of suburbia who grew up online. The child of a confectionary executive and a stay-at-home mother, the 24-year-old was the oldest of three brothers in Dacula, Georgia, a leafy exurb 37 miles northeast of Atlanta and part of Georgia’s “innovation crescent.” Kaderli has the ropy musculature and coiled energy of a rock climber, medium height with long black hair. He’s now a ward of the state and a convicted domestic extremist, currently in a Georgia prison for his part in a plot to murder an anti-fascist family. Kaderli and his coconspirators were members of a neo-Nazi guerrilla organization called the Base.

Rinaldo Nazzaro, an ex–FBI analyst and intelligence and defense contractor, founded the Base in 2018 while organizing under the aliases Roman Wolf and Norman Spear. It grew quickly into a clone of the Atomwaffen Division, recruiting young men through fascist corners of the internet and grouping recruits into geographic cells. The Georgia cell, to which Kaderli belonged under the alias Pestilence, was among the most active: They would organize shooting practices on a rural property, with Kaderli providing some of the firepower in the form of shotguns and semiautomatic rifles.

Through the Base’s online recruitment channels, Kaderli befriended James, a burly backwoods youth who read voraciously and taught himself Russian. In an interview with me last summer, James recounted his introduction to fascism. Much of his radicalization took place online, though he also had family who introduced him to fascism and white nationalism. Kaderli invited James into the Base, and the two bonded over their love of firearms and shooting in the Georgia woods.

As the Base grew in size and notoriety, Kaderli, James, and the Georgia cell organized training sessions at an increasing rate with comrades from across the South and East Coast. An October 2019 gathering was the largest of the sort: They sacrificed a ram, dropped LSD, and made pagan oaths. In the morning, those who could still stand took firing practice.

In that mix was a six-foot-four biker who went by the alias Pale Horse. The heavily tattooed ex-skinhead had grown close to Kaderli after they met outside the courthouse in Rome, Georgia. He’d gone on multiple shooting trips with Kaderli, noting his firearms proficiency and familiarity with tactical maneuvers. The notes were quite literal: Pale Horse was a cover identity for Scott Payne, a veteran FBI undercover agent tasked with infiltrating the Base.

At one Base gathering, they sacrificed a ram, dropped LSD, and made pagan oaths. In the morning, those who could still stand took firing practice.

Kaderli, Payne recalls, “was very self-assured and had a lot of piss and vinegar.” Payne, a onetime SWAT instructor, was struck by Kaderli’s ability to shoot rapidly and accurately with an AK-variant rifle and his familiarity with entry maneuvers like “slicing the pie” and “clearing a threshold.” It was clear to Payne that Kaderli was the right hand of the leader—Luke Lane—and had the attributes of a leader in the making himself: charisma, ideological conviction, and drive. Kaderli had already been visited by agents from the Atlanta field office and cautioned for posting a bomb-making manual online.

There was another element to the young fascist’s beliefs: a fascination with the occult and the Order of Nine Angles, an amalgam of neo-Nazism, satanism, and paganism created in Britain in the 1970s. When Kaderli and the others sacrificed the ram and made pagan oaths at one of the Base meetups, Payne recalls being chilled to the bone by Kaderli’s oath—“like listening to a slasher film.”

Adopted by Atomwaffen following Russell’s incarceration, the Order of Nine Angles was also prevalent in the Sonnenkrieg Division, a now banned British group that threatened Prince Harry. Kaderli, according to law enforcement sources and a former Base member, was in close contact with SKD members and produced their propaganda. “Jake was always driving people to get out there, train, buy guns, learn first aid, learn tactics,” says a former member of the Georgia cell who left because of concerns about Nazzaro’s ties to Russia. “He was one of the group’s main ideologues.”

By fall 2019, according to Payne, Kaderli, Lane, and other Base members were tired of shooting drills, hiking, and propaganda photo shoots. Kaderli got hold of a list of Georgia anti-fascists circulating online. Payne recalls Lane and Kaderli’s frustration with their political opponents outing the identities of right-wingers and confronting them at rallies. “The attitude was, How many of our brothers is this going to happen to before they hurt one of us? Let’s go kill one of them,” Payne says. “It was the Hatfields and McCoys.”

“They were putting together a list of liberal journalists and TV anchors, and I remember one of them saying, ‘Well, it’s a good thing we’re doing this family first because it’ll be a good starter for us,’ ” Payne says, recalling that one Base member spoke about his willingness to live on the street dressed as a homeless person, surveil a target for days, and shoot them with a revolver, disappearing without a trace.

Payne inserted himself into the plot, which targeted a Bartow County family. The plan, Payne says, was to kill them with firearms fitted to leave no casings and torch their house to erase all remaining evidence. “I have no problem killing a commie kid,” cell member Michael Helterbrand quipped to his coconspirators. Payne gathered enough evidence on a hidden recorder to prompt the FBI to swoop in and arrest Lane, Kaderli, and Helterbrand in January 2020. All three pleaded guilty to a raft of charges, including state conspiracy and gang membership, in 2021.

“Obviously the internet is a crazy place and there are many keyboard warriors out there, but the difference here is that these three guys plotted to murder people for their beliefs,” said assistant district attorney Emily Johnson at a November 2021 sentencing hearing, where Kaderli was sentenced to six years in state prison.

James did not get caught up in the murder plot: His faith in the Base had begun to crumble amid persistent rumors that Nazzaro, the founder, was not what he seemed; when The Guardian and the BBC later revealed Nazzaro’s identity, his residence in St. Petersburg, and his ties to Russian security services, that premonition was confirmed. “I was and am certain that Nazzaro is a Russian asset,” James says. “There were people that were talking about it in the Base, little peeps of that for a few months.”

James left the Base in fall 2019, ghosting the group’s chat rooms before publicly denouncing Nazzaro. Deleting his social media profiles and returning to the wooded hills of pine, oak, hickory, and ash near his hometown helped clear his mind. He soon found a new faith and community in Catholicism.

In an account written in early 2020, not long after leaving the Base, James detailed his estrangement. “If nothing else I’ve learned that people will always be driven by hunger and greed. And so as the group became more and more radical I was farther and farther detached,” he wrote. “I went from a hateful teenager who wanted to see society be destroyed, into a more thoughtful man, and I have more respect and understanding of society.”

As for his old comrade Kaderli, James believes that the lack of social connections or alternative worldviews outside of the far right will continue to hold him back. “Just like people in the military who don’t know what to do when they get out, it’s the same with these guys. If they abandon that worldview, all their friends and acquaintances, their identity will fade too. It’s frightening.”

With good behavior, Kaderli might be released on parole by next year. He says he is still firm in his beliefs but has not received any counseling about his extremist convictions that drove him to the edge of committing multiple homicides.

Jacob Kaderli, attorney Radford Bunker, and Michael Helterbrand in 2020. Image: Hyosub Shin/Atlanta Journal-Constitution/AP

“I’ve been in here four years in three different facilities, and you’re the first person to talk to me about anything ideological,” Kaderli said in a conversation in summer 2023. In each facility where Kaderli has served time, the prisoner-to-counselor ratio is a minimum of 150 to 1. “While I have remorse about what I’m in here for, I still believe National Socialism is an incredibly potent, functional ideology.” While his co-offenders have clicked up with prison gangs and been charged for weapons and violence, Kaderli says he has kept his nose clean and not incurred any disciplinary violations.

“Do we have a magic bullet that’d be suitable for the Jakes of this world? Of course not, but talking to a person and asking them questions at a minimum, we’ve got to do that,” says Pete Simi, the sociologist who studies the far right. Some of the current efforts at deradicalization, many run by former extremists, are “smoke and mirrors” because they are not evaluated consistently. “We don’t know whether they’re working or not,” Simi says. Some programs that have been tried include one-on-one counseling and violence diversion curricula directed at street or prison gang members, but to date there is no widely accepted best practice for deradicalizing far-right extremists.

Like many extreme-right Zoomers, Kaderli was mostly radicalized online, specifically by way of YouTube videos, extensive political conversations on Discord, and his immersion in an Iron March successor platform called Fascist Forge, where many members of the Base first met.

The appeal of National Socialism, Kaderli says, was that it offered a way out of the “defensive corner” he perceived white men were in during Trump’s presidency. “I’m proud of my ancestry and heritage, and there was so much talk of ‘bash the fash’ that I felt like I was being attacked for who I am.”

“I didn’t have any negative interactions about race or politics in real life,” Kaderli says of his adolescence in Dacula, where he was one of thousands of students at sprawling, diverse Mill Creek High School. Online, his teenage interest in libertarianism and political arguments with other users resulted in a now familiar trajectory down the rabbit hole to Mein Kampf and other staples of Hitler hagiography that led him to Fascist Forge, where he was one of the most active participants.

There was one experience in Kaderli’s background that backstops his belief in fitness, aggression, and might as essential—all key components of National Socialism in his view: the 2012 Sandy Hook massacre. Kaderli’s family moved to Dacula from Newtown, Connecticut, while he was in elementary school. He and his brothers had attended the school that Adam Lanza shot up.

“For me, the world had nothing worse in it up till then than the bugs or snakes I was catching in the backyard. Sandy Hook started my quest for knowledge. I didn’t wanna get shocked again when something like that happened,” he said. The elementary school massacre left him with the conviction that only strength and force could prevent such tragedies from befalling his loved ones. A firm belief in Second Amendment rights took him toward libertarianism, which exposed him to a set of anti-corporate beliefs that drew him toward National Socialism’s cursory critique of capitalism.

Through online neo-Nazi communities, Kaderli met a prolific neo-Nazi known as LionAW, an Atomwaffen Division member who played a major role in radicalizing and recruiting other minors to militant groups—and who has never been identified. According to a former Atomwaffen comrade, LionAW brought Giampa, the Virginia high schooler who ended up killing his girlfriend’s mother and stepfather, into the group as an “initiate,” or prospect. Giampa was found dead in Fairfax County Jail in mid-August. “We were actually trying to influence kids, manipulate kids,” says the former member, recalling how the group would dip into gaming platforms like Steam and Twitch to contact minors. “And it was successful. I remember that time period after Charlottesville when we had a huge influx of recruits, many of them underage.”

We were actually trying to influence kids, manipulate kids. And it was successful. I remember that time period after Charlottesville when we had a huge influx of recruits, many of them underage.

Former Atomwaffen Member

Fascism has always targeted adolescents and young men: The Hitler Youth produced decades of Nazi cadre. The British National Party and France’s Front National had youth wings that drew from reactionary student groups and the racist punk scene. Today this recruiting occurs in the online spaces that dominate teenagers’ social lives.

Even in prison, Kaderli is still connected to the online miasma that began his journey to a concrete cell. While Kaderli has abandoned the violent satanism of the Order of Nine Angles, he still views himself as a staunch Nazi and is well-versed enough in its history and beliefs that he can converse fluently about obscure 1930s schisms between Hitler and the National Socialist German Workers’ Party’s anti-capitalist wing led by Otto Strasser.

While he has been in prison, there’s been a major upheaval in Kaderli’s life: In September, his father died by suicide.

“We can’t grieve in here. It’s not like you can show a lot of soft emotions in prison,” Kaderli says, adding that he’s not sure he’ll ever lose the jailhouse habits of keeping his back to a wall or looking over his shoulder before passing through a doorway. Though he was able to watch a livestream of his father’s service and an aunt read his prepared remarks, his father’s death still feels abstract.

“I don’t know if I’ve accepted that it happened yet,” he tells me. And then: “I try not to entertain the thought, but my father might’ve not killed himself if I hadn’t gotten locked up.”

Exercising has helped Kaderli work through his loss, along with dipping into Beowulf and the spare offerings of prison libraries. He is aware of the far right’s growth in the four years since he was locked up and is enthused by the emergence of mixed martial arts–centered fitness groups for fascist youths known as “active clubs.”

“I’m really big on physical fitness: The one job I ever held was at a rock climbing gym, and that’s one reason I can’t take so many people in the movement seriously, because they can’t do 30 push-ups,” says Kaderli, who is currently working through the Georgia Department of Corrections at an auto parts factory, and has applied to college.

Robert Rundo is a throwback to an older form of American neo-Nazism: Think of the boots-and-braces skinheads of the 1980s who brawled with anti-racists at punk shows and featured as stock villains in 1990s indie films. The 34-year-old was neck-deep in gang life while growing up in Flushing, Queens, in the late 2000s, serving state prison time for stabbing a rival gang member in 2009. That stint, along with a prior juvenile term, opened Rundo’s eyes to white-power ideology in a classic example of the defensive reactive variety of extremism.

In a letter to me, Rundo identified the racial dynamics he encountered over 15 years ago during his juvenile sentence as a foundational experience for his ideological trajectory. “Out of the 300 youths, there were only two whites, including myself, in the whole place. So I learned real quick how people like me were viewed,” he writes.

Fifteen years later, Rundo is a prominent far-right influencer, the head of an international network of street-fighting white nationalist active clubs—and a federal inmate in Los Angeles, where he awaits sentencing in December on conspiracy to riot charges for leading a neo-Nazi street gang he founded, the Rise Above Movement (RAM), in assaults on counterprotesters at several political rallies in 2017.

“Back in the 1990s, the prison gangs didn’t really operate much outside the prison, except to support the guys inside,” says Mike German, a former FBI agent and Brennan Center fellow who infiltrated Tom Metzger’s White Aryan Resistance and other Southern California neo-Nazi gangs in the 1990s. According to German, “The prison gangs have become more political as the cops started letting them get away with clobbering anti-fascists.”

The prison gangs have become more political as the cops started letting them get away with clobbering anti-fascists.

Mike German, former FBI agent and Brennan center fellow

Two separate indictments in Virginia and California charged eight members, including Rundo, with conspiracy to riot. Federal intervention came before RAM could escalate: They’d been practicing drive-by shooting in the deserts east of Los Angeles. After the FBI raided his apartment, Rundo fled to Mexico before being apprehended in El Salvador. His ultimate destination was Ukraine, from which he’d been twice thwarted because the Department of Homeland Security added him to the United States No Fly List.

Rundo’s court saga has made him an international celebrity on the extreme right. After his case was dismissed on a technicality by a sympathetic federal judge in spring 2019, Rundo was released and relocated to Eastern Europe, where he lived a transient lifestyle while deepening his ties to the Old World’s extreme right: Ukraine’s Azov movement, Italy’s CasaPound, and hooligan firms of soccer clubs like Serbia’s Partizan Belgrade. He was extradited in August 2023 from Romania after ducking a US warrant and briefly rereleased in February, when the same judge dismissed his charges for a second time on the grounds of “selective prosecution,” only to be arrested once again in the company of fellow white supremacists. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reinstated his charges last summer, reversing the lower court judge’s dismissal. In early September, Rundo agreed to plead guilty to one charge.

Rundo set out to create a “3.0” white nationalist culture (1.0 being skinheads, 2.0 being the alt-right) that mimicked punk rock’s anti-systemic ethos. “Everything the left does, we should have a direct counter for,” Rundo opined in January while promoting his broader political project. He created yet another gang, this time larger than any of his prior efforts: the active-club movement of localized fight clubs now found in at least 33 states and across Western Europe. A 2023 Vice News report showed Rundo vetting recruits and coordinating actions from his Eastern European exile.

Unlike younger elements who were red-pilled online, Rundo’s milieu and Rundo himself arrived at racial “politics” in the confines of prison. Skinheads convicted of hate crimes and an increasing number of military personnel populate active clubs, including Daniel Rowe of the Evergreen Active Club in the Pacific Northwest and William Planer from Colorado’s Front Range Active Club, convicted of felony assault at a 2016 Sacramento melee.

Driven from what he calls “street activism,” Rundo’s role has evolved from that of gang leader to far-right propagandist. Rundo is looking at approximately two years in prison plus time served when he is sentenced later this year; he appears to have avoided charges for using a forged American passport while on the lam. “This is my new role; this is where life has taken me,” Rundo said in a March 2023 podcast, “and I’m content with my new role.”

What factors take people out of such violent circles? Sometimes, like with James, the threat of law enforcement and feeling manipulated by erstwhile comrades leads to estrangement. Sometimes a partner gives an ultimatum: me or the movement.

Connor, a former West Coast gutter punk and anarchist, traveled the full ideological horseshoe on his way from anarchism to National Socialism. He’d had a rough childhood, raised by a single mother and his grandparents. Social isolation at a series of industrial jobs, the fractiousness of his punk house and the music scene in his home city, and the simultaneous deaths of his grandfather and a close friend who overdosed sent him into serious depression. In response, Connor developed newfound interests in prepping, survivalism, and firearms.

A series of far-right podcasts and their attendant online communities drew him toward the Atomwaffen Division, whose style immediately captivated Connor. “They were edgy metal dudes in flecktarn, and their videos really caught my eye,” he recalled in a 2020 conversation. The group’s core text, Siege, “wasn’t far off from what I believed when I was a radical anarchist insofar as the general idea that civilization was coming to the point of collapse.” After a conversation with Brandon Russell, Connor was introduced to his local cell.

Members of the Base, a violent white supremacist group, pose.

The level of seriousness in Connor’s cell varied: Some knew how to build their own firearms, while others were more into black metal or shitposting. But they were active: Local universities were hit with Atomwaffen flyers. They went on urban exploring expeditions and filmed themselves firing assault rifles and shotguns while masked and in full camouflage. On a national level, other far-right groups were intimidated by Atomwaffen, particularly after Blaze Bernstein’s murder (which was not perpetrated by Connor’s cell).

That killing and Connor’s doxxing by anti-fascists upended his world. “I never wanted to get physical,” he recalled. But one day he woke up to find a flyer with his face, name, and photos of him in Atomwaffen gear on the windshield of his car. The flyer was plastered for a mile around his neighborhood as well as online.

“I stayed in my car that night, chain-smoking with my gun in my lap. I expected people to come to my house,” he said. Things unraveled rapidly: His girlfriend and their young daughter moved out. He lost his housing and his job. With no prospects, Connor moved across the country to live with another Atomwaffen cell. Rather than driving Connor out of the movement, his public unmasking had the opposite effect. “Getting doxxed radicalized me further,” he said. “I didn’t have anyone else lending me a hand aside from those guys, so I took them up.”

Across the country, Connor began to realize how different he was from his comrades, some of whom he labeled “broken, directionless young men.” Some were deeply immersed in the Order of Nine Angles, which he viewed as a macabre joke. Others preferred shitposting to holding a job. Another member of his cell was descending further into violent ideation, purchasing illegal guns and scheming to attack Atomwaffen’s enemies. (James and Connor asked to use aliases as a matter of self-protection.)

He’d found steady pay in construction work and a steady girlfriend outside of the movement. “I’d thrown myself into this setting blindly as a survival mechanism because it was all I had left—and I couldn’t stand it,” he told me. “It was like living a double life, being in Atomwaffen was like flicking a switch.” Connor began drifting away, coming home from work late and avoiding his housemates. The promise of a normal life with his girlfriend pulled Connor even further out of Atomwaffen.

One day he walked out of the house for good, leaving his flag, his fatigues, and his skull mask on his bed. The feds raided the house less than a month later. That was three years ago.

It’s been three years and he’s stayed completely out. Now he identifies as a Bernie Sanders–style socialist and has a house, a wife, and two young kids. “If I could build all of that despite what I believed,” says Connor, “then what good were my beliefs? How much did I really believe all that?”