The last time Tracy Cole remembered speaking to her 17-year-old son Alvin, he was at the mall. After she told him to be safe and that she loved him, he asked what’s for dinner. Alvin told his mother, “when I get home from the mall, I want a big plate like my dad,” Tracy recalled of that early February night in 2020.

Minutes after she spoke with Alvin, Tracy said her phone was flooded with worried calls. She recalled breaking news reporting that police had killed someone with a gun at the mall. Tracy couldn’t reach Alvin, so his family started searching for him. Since Alvin wasn’t at the Wauwatosa Police Department, nor the hospital, they tried the Milwaukee County Medical Examiner’s office.

When the medical examiner invited her inside, Tracy’s whole body went limp. This can’t be happening. That’s not my baby, she thought.

Tracy Cole, the mother of Alvin Cole, speaks during the listening session in Wauwatosa. Image: Isiah Holmes

Her husband of nearly three decades identified their son, and then wept.

Not long after, two Milwaukee Police Department (MPD) detectives stepped in and asked whether Alvin carried a gun. “None of ‘em ever say ‘my deepest condolence,’” said his mother, who later used her experience as a former funeral home worker to clean and dress her son for the last time.

Although from Milwaukee PD, the detectives actually represented an entity known as the Milwaukee Area Investigative Team (MAIT). In Wisconsin, investigations into deaths of civilians involving police officers are led by an uninvolved agency to help promote public trust. Since MAIT’s formation about a decade ago, the team has grown to include nearly two dozen neighboring law enforcement agencies which routinely investigate one another. MAIT’s investigations are reviewed by prosecutors who then decide whether officers will face charges for citizen deaths.

Wisconsin Examiner, in partnership with Type Investigations, has found that MAIT’s protocols grant officers certain privileges not afforded to the general public. In a typical civilian death investigation, police interrogate suspects to try to elicit an incriminating response. Officers being investigated by MAIT for civilian deaths, on the other hand:

- Are only interviewed as witnesses or victims, unless directed by a supervisor, rather than as suspects, usually without a Miranda warning and in the presence of a union representative or lawyer. In Wisconsin, crime victims are provided specific legal protections in terms of privacy and interactions with investigators — protections that are extended to police officers because of their official victim status after an officer-involved shooting.

- Officers may refuse to allow their statements to be recorded, despite MAIT protocols stating it is “accepted best practice” to record all interviews;

- Officers may make “additional statements” after viewing video evidence.

Wisconsin Examiner/Type reviewed 17 investigations conducted by MAIT from 2019-2022, including the one that involved Cole. No officers were charged after any of these incidents. MAIT’s investigations rarely result in criminal charges against officers for citizen deaths.

Taleavia Cole in a protest crowd at Wauwatosa’s Cheesecake Factory restaurant in 2020. Image: Isiah Holmes/Wisconsin Examiner

Meanwhile, seven families interviewed by Wisconsin Examiner/Type, including the Coles, describe experiencing suspicion, hostility, stonewalling, or emotional disregard from police investigators. Some agencies have also monitored families of people killed by officers, even years after their loved one’s death.

MAIT’s commander, Greenfield Police Assistant Chief Eric Lindstrom, declined to comment for this story, as did a committee that oversees the team. But several of the member agencies responsible for shootings and investigations reviewed in our analysis disputed the idea that MAIT favors officers.

Wauwatosa PD’s spokesperson said in a statement that the department “has full confidence in the impartiality and transparency of MAIT investigations, ensuring accountability to the families involved, the officers, and the public.” A West Allis PD spokesperson said West Allis MAIT investigators “conduct thorough, fair, and impartial investigations which enable a District Attorney to make a finding regarding an incident.”

Cole’s shooting was the first of 10 MAIT investigations in 2020. He was also the third person killed by the same Wauwatosa officer in a five-year period.

Shapeshifting Narratives

Alvin’s older sister Taleavia Cole was still at Jackson State University in Mississippi when she learned her little brother was dead. “It’s been difficult without him,” she told Wisconsin Examiner/Type, four years after her brother’s killing. “Although he was the little brother, he was definitely the big brother…He was a protector. He’s not about to play about his sisters and his mama.”

Taleavia gradually pieced together what happened to her brother by talking to family and friends, and by looking at local news reports. Alvin allegedly flashed a handgun during an argument and fled mall security with his friends as police arrived. Wauwatosa officer Joseph Mensah was one of several responding officers. Mensah chased after Cole and, as they ran, a single gunshot rang out in the darkened parking lot.

Mensah later told MAIT investigators that he neither saw a muzzle flash nor knew who had fired. The radio broadcast “shots fired,” and Cole fell to his hands and knees. “Don’t move,” some officers yelled while others demanded he “drop the gun” or “throw it.” Then five more shots boomed with dash footage capturing a voice yelling, “stop, stop!”

A Wauwatosa police squad. Image: Isiah Holmes/Wisconsin Examiner

Both Mensah and fellow Wauwatosa officer Evan Olson told MAIT that Cole pointed a gun after he fell. But four years later, a judge determined the officers gave “conflicting testimony.” Mensah said Cole pointed a gun directly at him and did not see it being pointed at anyone else. Olson, who was standing apart from Mensah, said the gun was pointed “westbound” toward Olson.

Meanwhile, Wauwatosa officer David Shamsi didn’t mention seeing the gun raised at all. Squad video that February night captured Shamsi telling an unknown individual, “I didn’t see him have the gun in his hand, it was on the ground.” In July 2020, when he spoke with the district attorney’s office, it appears that Shamsi changed his story, saying he saw Cole “raise his firearm,” according to a Wauwatosa PD administrative review of the shooting.

Shamsi later resigned from Wauwatosa PD while on military deployment. He was later hired by the FBI. In a 2024 ruling, U.S. District Court Judge Lynn Adelman wrote that Shamsi testified in a deposition that “he [Shamsi] had sight of the gun at all times, and that the gun did not move at any time before Mensah shot Cole.”

Mensah, Olson, and Shamsi all declined to comment for this story via representatives.

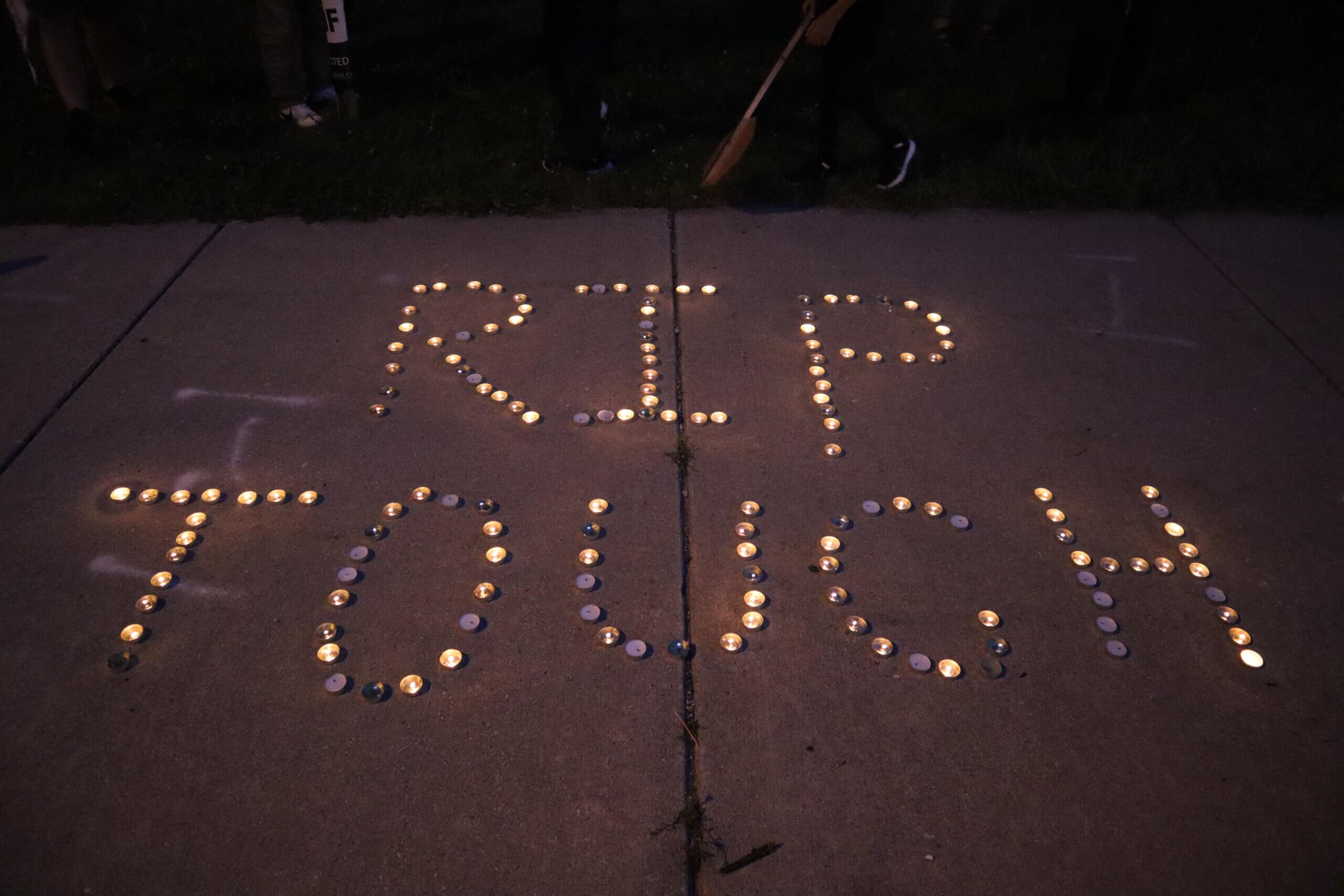

Activists hold a candle-light vigil for Roberto Zielinski, who was killed by a Milwaukee PD o cer in late May, 2021. This case was investigated by Waukesha PD as part of the Milwaukee Area Investigative Team (MAIT). Besides Alvin Cole, Zielinksi’s shooting had an officer change their story. Image: Isiah Holmes/Wisconsin Examiner

It wasn’t the only time an officer’s story changed during an investigation of police who killed a citizen. After a 2021 Milwaukee PD shooting, an officer who’d contradicted his partner by telling MAIT that a gun hadn’t been pointed at them later changed his story when talking to the district attorney.

Mensah was the only officer to shoot Cole. As the teen struggled to breathe, officers handcuffed Cole and assessed his wounds. Police and medics soon arrived, and West Allis police officers started a log documenting everyone entering and leaving the crime scene while other officers combed the area for witnesses.

Slipping around MAIT’s protocols

It didn’t take long for the investigation into Cole’s death to diverge from the official procedure. MAIT’s protocols direct supervisors to “ensure that the involved officer is separated from other witnesses and removed from unnecessary contact with other officers.” This is intended to prevent the contamination of officer statements.

Yet at some point that night, Olson became Mensah’s “support officer,” keeping Mensah company and comforting him, even though Olson had both witnessed the shooting and aimed his own weapon at Cole. Support officers are generally tasked with helping fellow police personnel cope with the stress of the job.

After the shooting, according to MAIT investigative reports, Wauwatosa officer Maria Albiter was told by a supervisor to sit with Mensah. Unlike Olson, Albiter had not witnessed the shooting. Albiter told investigators, however, that Olson then came by and said he’d sit with Mensah instead.

MAIT’s interviews with Olson and Mensah neither mention Albiter, nor that Olson and Mensah had been alone together.

Cole’s death investigation doesn’t address this apparent violation of MAIT’s protocols. An internal review of the shooting by Wauwatosa PD denied that there was any evidence of statement contamination due to Olson and Mensah not being separated.

This instance of officers not being separated also wasn’t an anomaly. In six of the 17 MAIT investigations reviewed by Wisconsin Examiner/Type, officers were not separated after a civilian death, and some were captured on camera talking with each other about the incident.

Protesters march in the summer of 2020 in Wauwatosa, one carries a sign with an image of Alvin Cole. Image: Isiah Holmes/Wisconsin Examiner)

There were other indications of potential bias related to the Cole investigation. In February 2020, two detectives from nearby Greenfield PD joined the investigative team. One of them was Det. Aaron Busche, then vice president and now president of the Greenfield Police Association. Later that year, as protests mounted against Mensah for his role in multiple shootings of civilians – but before a charging decision in Cole’s shooting had been made – the Greenfield Police Association donated $500 to Mensah’s GoFundMe page, which raised money to cover his legal expenses, despite Busche’s prior involvement in the Cole investigation. Busche did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

Officers may refuse to be recorded when interviewed by investigators, making it harder to track inconsistencies or confirm details in their stories. Like every other investigation reviewed for this story, Cole’s file suggests MAIT investigators did not record most of the officers’ statements. Only two officer interviews specify that they were recorded.

MAIT routinely conducted unrecorded interviews with officers. After one September 2021 shooting, every officer who fired a weapon refused to be recorded. In another 2021 case, 80% of all interviewed officers refused to be recorded by MAIT detectives.

Nearly two-thirds of MAIT’s investigations reviewed by Wisconsin Examiner/Type document such refusals. By contrast, MAIT’s protocols state that all civilian witness interviews must “at least be audio recorded” and that investigators “will be equipped with portable audio recorders for this purpose.” While they acknowledge citizens may “refuse to be tape recorded or videotaped,” in practice, civilian witness interviews seem to be recorded far more often than officers.

Both the Waukesha and Wauwatosa police departments confirmed with Wisconsin Examiner/Type that their MAIT investigators did not record officer statements for investigations reviewed for this story. A spokesperson from Milwaukee PD referenced protocols from the Milwaukee County Law Enforcement Executives Association, which state “the officer cannot be forced to give a recorded statement.”

Although recorded interviews cannot be forced, West Allis PD stressed that they have obtained voluntary statements from officers “in almost 100% of the cases.”

A West Allis Police Department squad car on the scene of an officer-involved shooting in Wauwatosa in December 2020. Image: Isiah Holmes/Wisconsin Examiner

Civilians subjected to police questioning face far more pressure. After Cole’s shooting, one 14-year-old boy who was with Cole’s group of friends was questioned by MAIT for over an hour, under Miranda warning and without his parents or a lawyer.

In the interrogation video, detectives asked, “Right before he got shot, what did he do?” The boy replied, “I don’t know…I was worried about me. I was trying to get away…I’m looking back and running at the same time.” Later, the detectives encouraged the boy to “think real hard, and just focus on it,” and said, “you have nothing to owe this guy,” referring to the deceased Cole.

Both detectives repeatedly stressed the importance of honesty. More than an hour and 10 minutes into the interview, after the detectives again asked what happened, the boy replied, “I’m telling you what I remember. I can’t really tell y’all something I don’t know, because then if I tell y’all something that’s a lie then I’m going to get in trouble.”

When asked about this interrogation, the West Allis spokesperson said the department “follows all laws pertaining to juvenile interviews, including during MAIT investigations.”

“I’m telling you what I remember. I can’t really tell y’all something I don’t know, because then if I tell y’all something that’s a lie then I’m going to get in trouble.”

A 14-year-old boy who was interrogated by West Allis detectives during the MAIT investigation into Alvin Cole’s death.

The state law that later led to MAIT’s creation aimed to make investigations independent so that a police force is not investigating itself for potential wrongdoing. But Wisconsin Examiner/Type found that in 82% of the cases reviewed for this story, the agency involved in the death also participated in parts of the investigation.

After one Waukesha PD shooting, officers transported weapons they’d fired back to their department before they could be located by MAIT investigators. (A Waukesha PD spokesperson told Wisconsin Examiner/Type that this was accidental, and that officers contacted MAIT once they realized the weapons had been used in the shooting.)

In another shooting by Wauwatosa PD, a wounded woman who’d been shot by officers called detectives, asking why Wauwatosa officers guarded her hospital room and wouldn’t allow her family to visit.

Police block off the scene of where Tineisha Jarrett was shot by a Wauwatosa officer in December 2020. Jarrett would later call investigators to ask why Wauwatosa officers guarded her hospital room and wouldn’t allow family visits. Image: Isiah Holmes/Wisconsin Examiner

In 2019 after a Milwaukee PD shooting, a Milwaukee detective helped MAIT interrogate the victim’s girlfriend. In another 2021 case Milwaukee PD provided medical assistance to someone fatally shot by Greenfield PD, and then served as the lead MAIT investigating agency, even interviewing its own officers. In other cases law enforcement from involved agencies drafted and executed search warrants for the homes of people killed by police.

None of these activities are strictly against the law, even if they raise questions about the neutrality of the investigators. A Milwaukee PD spokesperson wrote in an emailed statement that in the 2021 Greenfield shooting, its officers were not directly involved in the shooting as defined by Wisconsin statute. Likewise, a Wauwatosa PD spokesperson said that “each situation and investigation conducted by MAIT is unique” and that MAIT works closely with the involved agency to “determine the best approach”, which may include the involved agency “potentially conducting or assisting in the investigation.”

Cole was Mensah’s third fatal shooting over a five-year period. The district attorney’s office declined to charge Mensah in all three shootings, stating that his use of deadly force was reasonable, justified, or privileged. A civil lawsuit filed over Cole’s death in 2022, however, raised questions about the shooting.

After hearing arguments in 2024, Judge Adelman ruled that the lawsuit could go to trial. Explaining his ruling, Adelman wrote, “Based on the conflict between the testimony of Olsen and Shamsi, on the one hand, and Mensah, on the other, it is impossible to know what happened and whether Mensah’s use of deadly force was reasonable.”

Trying to cover something

For families of people killed by police, trust is often broken as soon as detectives walk through the door.

When MAIT investigators came to the Anderson family’s home back in 2016, the Andersons did not yet know that their son, Jay Anderson Jr., was dead.

Around 3 a.m., Mensah had noticed Anderson’s car sitting alone in a park. Anderson’s family says that he’d been out celebrating his birthday a few days early, and was sleeping off the intoxication. MAIT reports state that after waking Anderson in his car, Mensah noticed a handgun beside the 25-year-old.

Less than 30 seconds of mute dash footage captured Mensah pointing his weapon at Anderson, who was sitting in the driver seat with his hands raised. Mensah shot Anderson six times after his hands lowered.

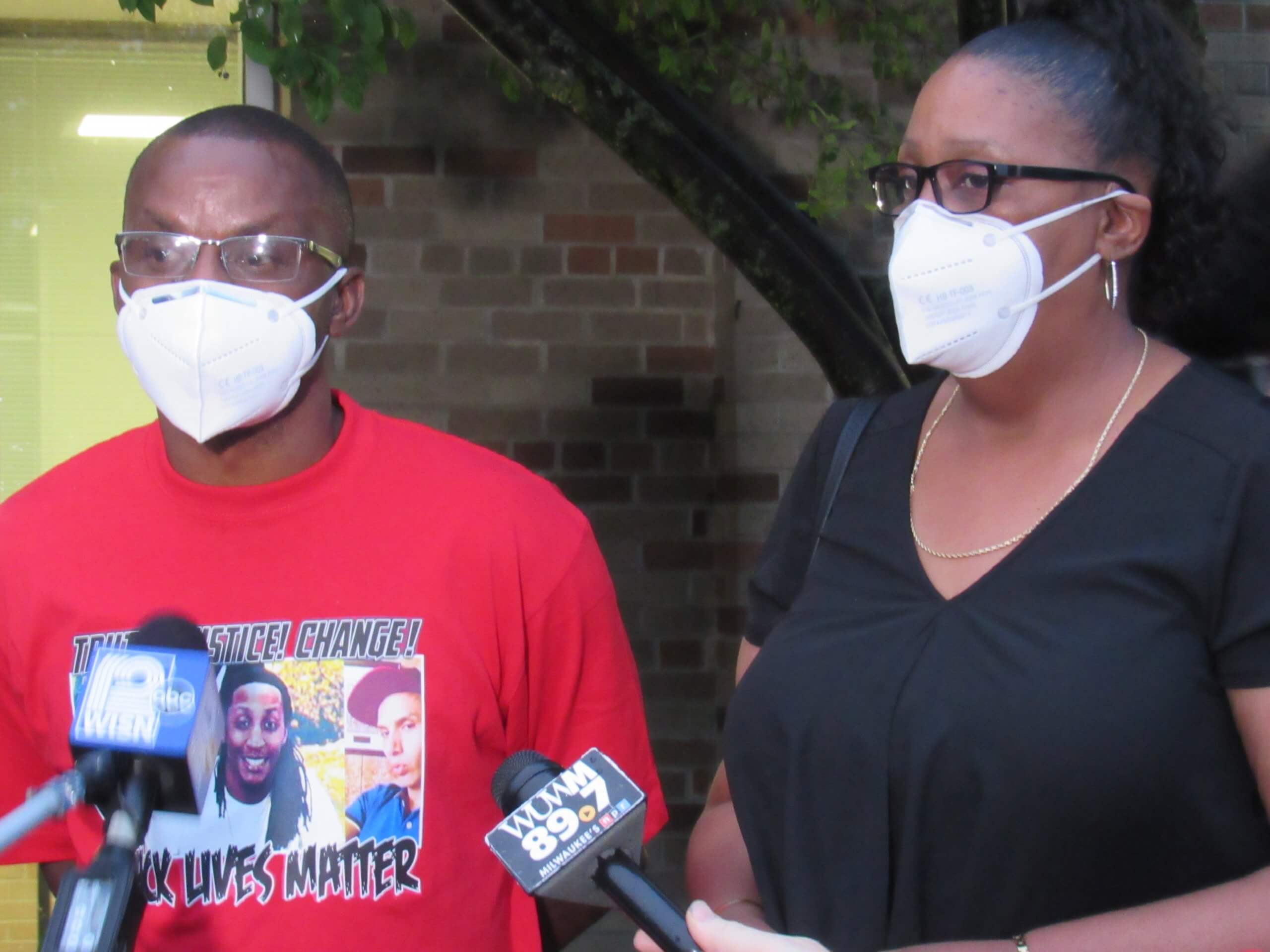

Jay Anderson Sr. and Linda Anderson speak with press in 2020. Image: Photo by Isiah Holmes/Wisconsin Examiner

Jay Sr. recalled that Milwaukee PD detectives presented a picture of his son “with a big Glock 40 hole in his jaw” so he could identify him. His wife Linda said the detectives never expressed sympathy. Instead, she recalled, they started interrogating the family. “It wasn’t, ‘Oh we’re sorry this happened to your son,’” she said. “It was: ‘Do he smoke? Do he sell pot?’ It was them trying to build a case, from the minute that they killed my son.”

An MPD spokesperson said that it “takes complaints seriously” and encourages anyone concerned about the behavior of MPD officers or detectives to file a formal complaint through the civilian-led Milwaukee Fire and Police Commission.

It wasn’t, ‘Oh we’re sorry this happened to your son’…It was them trying to build a case, from the minute that they killed my son.

Linda Anderson, the mother of Jay Anderson Jr.

Years later, a different mother also came away feeling suspicious after her interaction with MAIT detectives. Markeisha Evans who, like the Coles and Andersons, lives in Milwaukee, recalled an unexpected visit by Waukesha detectives. When they arrived on a February night in 2022, the detectives first asked whether her son, Keishon Thomas, lived there. The 20-year-old had gone out that night and she was waiting for him to return. Evans said that the detectives then suddenly asked, “Was he sick?”

Evans said that Thomas was healthy. “After them asking me a number of questions — and this about 15 or 20 minutes in — they tell me my son ‘didn’t make it’” … and that “he passed,” Evans told Wisconsin Examiner/Type.

Milwaukee officers had arrested her son earlier that night on drug charges. Thomas was later found unresponsive in his cell at a district station. Milwaukee PD said that Thomas consumed and overdosed on drugs he’d allegedly managed to hide from the officers who handcuffed, searched, and booked him. Two Milwaukee officers were later convicted on charges related to falsifying cell check reports and neglecting to get Thomas medical attention after he’d ingested drugs. One officer paid a $5,000 fine, avoiding prison time and probation, while the other received probation.

The way the detectives opened their questioning without first saying Thomas was dead lingers in his mother’s mind. “I thought that it was inappropriate,” said Evans. “Almost like they were trying to cover something.”

A spokesperson for the Waukesha PD apologized that detectives made Evans feel this way, but said that detectives must develop foundational information with interviewees, and denied that detectives were looking for a way to excuse Thomas’ death.

Targeting families

Some MAIT agencies have also closely monitored family members who join protests after their loved ones are killed by police.

Taleavia Cole became a regular speaker at protest rallies after her brother’s killing. “She was out there and she was good at it,” Linda Anderson told Wisconsin Examiner/Type. Wauwatosa PD noticed as well.

“She’s a leader or informal leader, and people follow leaders,” Wauwatosa PD Capt. Luke Vetter said during a civil deposition in a lawsuit against the city for their handling of protests.

Taleavia Cole at a protest in Wauwatosa during the summer of 2020. Image: Isiah Holmes/Wisconsin Examiner

The Cole family’s attorney pressed Vetter to explain how a family member who spoke out about her relative being killed by police became a suspicious person to police in her own right.

“We recognize that people will listen to her, and will follow her, and if she has a plan in mind or an event in mind, that she will garner support. And that is something that we have to just be careful of, and watch, and monitor,” Vetter said in the deposition. When asked why Taleavia was considered a threat Vetter described her as “passionate about her position” and that “sometimes she is more adversarial than she should be and I think sometimes groups will follow that.”

Like her mother, sisters, attorneys, and dozens of others including this story’s author who reported on the protests, Taleavia was placed on a “target list,” as Wauwatosa police called it in an email, naming protesters and their allies in 2020. Some MAIT member agencies have also monitored the Coles, the Andersons, and other family members of people shot by police using an internal database that compiles confidential personal information ranging from car registrations to home addresses, criminal histories and more. The Milwaukee PD, which frequently searched the names of Keishon Thomas’ loved ones in this database, said that this is often done to identify contact information and next of kin. The department acknowledged that in at least one instance, a database search was done to identify a loved one of Thomas after “a social media post was discovered.”

Police block a road during the October Wauwatosa curfew in 2020, just after having red rubber bullets and tear gas. Image: Isiah Holmes/Wisconsin Examiner

On Oct. 7, 2020, the Milwaukee County district attorney announced Mensah would not be charged for shooting Cole. Wauwatosa declared a curfew, anticipating protests over the decision. That night, some in the protest crowd broke windows, and looted a gas station. The following night, members of Cole’s family was arrested for violating curfew as they rode in a protest caravan. Police depositions conceded that they were unable to develop probable cause linking the Coles to any destructive behavior.

Taleavia was briefly jailed in Waukesha County and her phone was confiscated by Wauwatosa PD for 22 days. During that time, according to a motion to return seized property filed in the Milwaukee County Circuit Court, “her Facebook and Instagram has disappeared,” and her iCloud account with attorney-client information had been “tampered with.”

Wisconsin national guard during the October 2020 curfew in Wauwatosa. Image: Isiah Holmes/Wisconsin Examiner

Wauwatosa Special Operations Group Detective Joseph Lewandowski, who was both a MAIT detective and peer support officer and considered Mensah a friend, also identified Wauwatosa’s mayor as one of four “higher value” targets in 2020, due to his perceived support of protests. Interrogating a protester through a balaclava mask emblazoned with a thin blue line logo in 2020, Lewandowski said of Cole and others killed by Mensah, “he chose that. Just like the other ones. They all chose that.”

Lewandowski apologized for his behavior during a civil deposition, and added that “they [Mensah’s shooting victims] still have families and those families are victims as well. And I believe there was a chance that that sight picture was lost.” He also said that police deserve “a baseline of support” and answered in the affirmative when an attorney asked whether public officials should “blindly support the police.” The Wauwatosa PD declined to comment further on Vetter and Lewandowski’s deposition testimony.

Later in 2021, members of the public who were entering court hearings on Mensah’s 2016 shooting of Anderson were monitored by Milwaukee County Sheriff’s drones. Special prosecutors also later said that they declined requests from Milwaukee PD to keep Wauwatosa PD apprised of meetings with the Andersons, so that Wauwatosa could position squad cars nearby. The hearings, initiated under Wisconsin’s John Doe law allowing a judge to review a case where prosecutors already declined to file charges, found probable cause to charge Mensah with homicide by negligent use of a dangerous weapon.

In his ruling, Milwaukee County Circuit Court Judge Glenn Yamahiro blasted the Anderson MAIT investigation. Wauwatosa detectives including Lewandowski interviewed witnesses and attended Anderson’s autopsy. Anderson’s gun and body were also moved from his car before Milwaukee PD arrived to investigate.

“If the goal is to maximize objectivity and minimize bias, it will require a legislative alternative to having local law enforcement agencies investigate each other in officer-involved deaths,” said Yamahiro. “It is unreasonable to ask them [local law enforcement] to turn around and investigate each other in matters as serious as these, and for them to suddenly set those relationships aside.”

Special prosecutors still declined to charge Mensah.

“If the goal is to maximize objectivity and minimize bias, it will require a legislative alternative to having local law enforcement agencies investigate each other in officer-involved deaths.”

Milwaukee County Circuit Court Judge Glenn Yamahiro

MAIT was born in an attempt to improve upon the previous status quo. Stephen Rushin, a law professor and dean at Chicago’s Loyola University, called Wisconsin’s law mandating independent investigations “unique” and “not representative of how most places across the country do it.” Rushin said that other police departments in the U.S. tend to investigate themselves after civilians die in custody or are killed by police in shootings.

But as Judge Yamahiro noted, outsourcing investigations to neighboring police forces doesn’t fix the problem of conflict of interest. Ricky Burems, a retired Milwaukee PD homicide detective, argues that police are indoctrinated to always protect one another. “The issue is police culture in general,” said Burems, who investigated police shootings and deaths during his career. Burems compares the relationship among police officers to the instinctive loyalty between siblings. “It’s truly a brotherhood…We are trained to protect each other.”

Linda Anderson, the mother of Jay Anderson Jr, and attorney Kimberley Motley address media after special prosecutors decline to charge Joseph Mensah. Image: Isiah Holmes/Wisconsin Examiner

Burems fears that investigators fail to humanize a victim’s family. “If the lives of the victims were valued as human beings, this could not happen,” said Burems, who testified as an expert witness in Jay Anderson’s John Doe hearings. “If they valued Jay Anderson’s life, Mensah would not have been able to kill Alvin Cole.”

When asked about this characterization, an MPD spokesperson wrote in an email that “we continuously strive to serve our community professionally and respectfully. We also recognize the need for additional resources for victims of crimes, which is why we created two new Victim Specialist positions within our Criminal Investigations Bureau, and hope to fill these in 2025.”

“It’s truly a brotherhood…We are trained to protect each other.”

Ricky Burems

A West Allis Police spokesperson also objected that “the claim that MAIT actively works to protect fellow officers is categorically false, without merit, and without a factual basis. Reckless statements such as this erode trust in the criminal justice system and adversely impacts individuals who heavily rely upon the criminal justice system.”

Oversight and accountability

MAIT’s protocols state that a police agency’s reputation and credibility with the community “are largely dependent upon the degree of professionalism and impartiality that the agency can bring to such investigations,” and that “instances where citizens are wounded or killed can have a devastating impact on the professional integrity and credibility of the entire law enforcement agency.”

Yet the team lacks transparency. MAIT is overseen by a committee made up of eight local police chiefs and members of the Milwaukee County Law Enforcement Executive Association Board. Team members communicate through encrypted chats while the committee holds votes in non-public committee meetings to choose committee leaders, set policy, and decide the team’s future.

Releasing death investigations after a prosecutor’s decision is supposed to offer public transparency. Nevertheless, open records practices across MAIT’s member agencies are inconsistent. The Waukesha PD, for example, has a web page dedicated to its MAIT releases declaring that states, “the documents below are posted in the interest of transparency.” Below that line the page is blank.

When asked about the empty web page, a Waukesha PD spokesperson said that it was due to human error when the city’s website was rebuilt and that they are working to re-post the case files.

Leon Todd, executive director of Milwaukee’s civilian-led Fire and Police Commission, said that since MAIT is made up of multiple agencies, “there is no single entity that has oversight over MAIT.”

Families are left with little recourse other than the courts. Yet criminal charges against officers are rare, as are victories in civil court.

“It’s important to not overlook the fact that these suits can often be the only way that people can get any measure of justice in these cases,” said UCLA law professor Joanna Schwartz, author of the book “Shielded, How The Police Became Untouchable.” Discipline or prosecution of officers is “exceedingly rare,” said Schwartz, making civil suits “the only avenue, and they’re certainly the only avenue by which a person could be compensated for that wrongdoing. In addition, these suits often are critically important ways of unearthing information about department practices.”

After resigning from Wauwatosa PD, Mensah was hired at the Waukesha County Sheriff’s Office, where he’s a detective and has investigated a death at the Milwaukee County Jail.

Detective Joseph Mensah testifying in 2025 before the Senate Committee on Judiciary and Public Safety in favor of protecting police officers from John Doe hearings. Image: Isiah Holmes/Wisconsin Examiner

After the protests, Vetter briefly served as Wauwatosa’s acting chief before Chief James MacGillis was hired in 2021. Olson resigned from Wauwatosa PD in good standing in December 2023. He now works at West Allis PD, and serves as the treasurer for the West Allis Professional Police Association. Lewandowski was promoted to patrol sergeant at Wauwatosa PD after being disciplined for the higher value target controversy, and was moved out of both the Special Operations Group and MAIT. The Milwaukee PD has repeatedly denied allegations that it surveils the families of people killed by police.

Declining to comment on the Cole family or surveillance they may have experienced, a Wauwatosa PD spokesperson said in a statement that “our focus is on the future” and that the department is “committed to our mission of providing dedicated service and protection to all.”

MAIT continues its investigations, including looking into the killing of an unhoused man by out-of-state officers during the 2024 Republican National Convention. In an interview with WOSU Public Media, MAIT’s commander, Greenfield Assistant Chief Eric Lindstrom, said, “all of the agencies that are members of this team really feel it provides a benefit.” The team claims that other agencies nationwide have modeled their own teams on MAIT.

Taleavia Cole, the older sister of Alvin Cole, addresses a group of protesters crowd

alongside Jay Anderson Jr.’s parents in 2020. Image: Isiah Holmes/Wisconsin Examiner

Teleavia Cole still has questions about the decisions officers, investigators and prosecutors made in her brother Alvin’s case. A federal jury trial in her family’s civil case is set for March 17, 2025.

Losing Alvin was difficult for the Cole family, yet it also brought them closer. “It was difficult for my parents, but with us being a close family, and with me just being who I am, I’m going to make sure we figure things out,” Taleavia Cole told Wisconsin Examiner/Type. “We want to do more for him,” she added. “We want to tell his story.”