This article was produced in partnership with The Nation, with support from the Puffin Foundation.

Rosalia Manuel had worked for McDonald’s for more than 20 years when she was suddenly fired in 2022. Until then, she had been considered “the best employee,” she said, and had worked her way up to shift manager at a location in Saratoga, California. It was a role she took seriously.

That March, after a coworker confided to her that a different shift manager had been following her around, making suggestive comments, and coming on to her, Manuel reported the behavior to the store manager above her. Manuel had never been trained on how to respond to incidents of sexual harassment, she said, but she felt that it was her responsibility to do something.

The shift manager who had been harassing Manuel’s coworker never appeared to receive any discipline. Instead, in July, the store manager suspended Manuel for a week for allegedly failing to take her lunch break on time. When Manuel returned to work, she was told she was being fired for insubordination, according to a complaint she filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). Manuel had a different theory. She called the McDonald’s corporate human resources hotline to complain that she had been fired for reporting sexual harassment. She was told they would investigate, she said, but she never heard back.

The harasser, however, kept working for McDonald’s. In the fall of 2022, at another McDonald’s location in San Jose, the woman began telling Sindy Pamela Mejia, a new employee, that she had a nice body. According to a complaint Mejia has filed with the California Civil Rights Department, she would simulate sex acts, talk about her sex life, and say things like “Ay, qué rico”: How delicious. She quizzed Mejia about whether she had a husband or a boyfriend, Mejia told me. When Mejia rebuffed her, the woman started bullying her, she said, making fun of her for speaking Spanish and for being Honduran.

Mejia didn’t know what she was supposed to do. When she started working at McDonald’s, she was required to watch several onboarding videos. Two of the videos, each about a minute long, advised employees not to touch each other and to say “Excuse me” if they accidentally bumped into somebody—but they didn’t specify any procedures for responding to sexual harassment, Mejia said.

In December, Mejia decided to report the behavior to her manager. But nothing was done, she said; the harasser once again appeared to escape repercussions. Instead, in January 2023, Mejia’s manager reduced her schedule from 40 hours a week to nearly half that, and then to just 13 hours by March—retaliation for reporting the harassment, Mejia said in her complaint.

Mejia decided to report the harassment again in August 2023, this time to an HR representative, but the situation only grew more unbearable in the months that followed, she said: Her harasser was emboldened and told Mejia that the lack of discipline meant she could do whatever she wanted. She started denying Mejia breaks, even to use the bathroom, and refusing to put in her lunch order so she could eat, Mejia said. Mejia was so disturbed that she would skip meals during her shifts and cry in her car instead.

“Nobody seemed interested in helping me with this situation,” Mejia said in Spanish through an interpreter. The harassment stopped only when the woman left the San Jose McDonald’s in May 2024.

McDonald’s did not respond to requests for comment on the specifics of Manuel’s or Mejia’s allegations. Manuel’s EEOC complaint was settled in March 2023. The California Civil Rights Department has not yet issued a ruling on Mejia’s complaint.

Mejia still works at the McDonald’s in San Jose; it’s difficult to find another job that allows her to pick her children up from school. But as a single mother of two who is now working fewer hours, she said, she has struggled financially, and has taken out loans to pay her rent, buy groceries, and pay her bills. “No puedo sobrevivir”—I can’t survive—she said.

“The best worker”:

Rosalia Manuel was fired in 2022 after having worked at McDonald’s for more than 20 years. She believes it was because she reported that she had been sexually harassed by a manager. Image: Courtesy of Rosalia Manuel

Four years ago, McDonald’s promised to take action after allegations emerged of stunningly high rates of sexual harassment at its restaurants. A 2020 survey had found that three-quarters of female nonmanagerial employees had experienced sexual harassment. The company had faced not just a historic nationwide strike over the problem but dozens of lawsuits accusing it of failing to prevent and address harassment. That same year, The Nation published its own investigation based on a review of 24 legal complaints and conversations with restaurant workers who described rampant verbal and physical harassment, including being grabbed, groped, and threatened with rape. The CEO of McDonald’s at the time, Steve Easterbrook, was fired and then sued by the company later that year for engaging in multiple sexual relationships with subordinates against company policy.

In response to the bad press, McDonald’s announced in April 2021 that it would implement “global brand standards” to create “a culture of physical and psychological safety for employees and customers through the prevention of violence, harassment and discrimination.” The standards would apply, for the first time ever, to franchised as well as corporate-owned restaurants—a significant development given that, globally, 93 percent of McDonald’s locations are franchised. In the past, the company had declined to enforce corporate rules at its franchises and argued that it couldn’t be held liable for sexual harassment at such locations.

Under the new standards, the company said it would require restaurants to establish policies and provide trainings to combat sexual harassment, as well as reporting processes and annual employee and manager surveys. The standards were rolled out over the course of 2021 and took effect in January 2022. All McDonald’s locations were meant to be “assessed and held accountable” to the standards by that date.

Despite the company’s claims that the new standards would fix the problems, an investigation by The Nation and Type Investigations found that little changed in many McDonald’s locations after the standards went into effect. According to legal complaints from 20 workers in California, Florida, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Texas, not only has sexual harassment continued in these places, but when employees have reported it in the hopes that the company would address the situation, nothing was done. Instead, in several cases, workers like Manuel and Mejia said they were punished for coming forward by having their hours cut or even losing their jobs.

There is a likely reason why little has changed, experts say: The global brand standards have been inadequate to the task of preventing sexual harassment.

McDonald’s has not shared the details of the global brand standards publicly. Despite its efforts to keep them secret, however, The Nation and Type Investigations obtained an internal corporate document titled “2022 U.S. People Brand Standards Visit” that provides insights into what the standards consist of. This document details the criteria used by McDonald’s to evaluate whether its restaurants and franchises were in compliance with the brand standards after they were implemented, revealing how McDonald’s enforces its new solution. What this document suggests is that, while the requirements adhere to a certain logic for how to prevent and address sexual harassment, they are too broad and vague to be effective.

Eve Cervantez, a lawyer who is leading a class-action lawsuit against McDonald’s, said, “I have not seen that there has been any diminishment in complaints of sexual harassment at McDonald’s, and I have not seen any better response to allegations of sexual harassment since January 2022.” She added, “There’s no way the standards could have fixed the problem, because they’re not really addressing the problem.”

A McDonald’s spokesperson declined to provide details of the global brand standards to The Nation and Type Investigations. In response to a detailed list of questions about the global brand standards and sexual harassment in its restaurants after the standards went into effect, McDonald’s reiterated that it was committed to safeguarding workers and preventing abuse.

“Even one allegation of sexual harassment is too many. McDonald’s believes that every single individual who works under the arches deserves to experience a safe, respectful, and inclusive workplace,” the company said in a statement. “To support our commitment to these values, we offer strong guidance aimed at preventing discrimination, harassment, and retaliation. At our company-owned restaurants, this includes conducting trainings for all employees, providing resources and materials in the restaurants and offering multiple avenues for reporting concerns. We also provide Franchisees with optional tools and other resources aimed at making their employees feel valued, respected, and supported.”

McDonald’s has opposed the granting of class-action status for Cervantez’s case, Jamelia Fairley and Ashley Reddick v. McDonald’s, which has been ongoing since 2020 and includes complaints from dozens of restaurants in Florida. The company argues that the plaintiffs don’t have enough in common, haven’t provided sufficient evidence to establish a pattern of sexual harassment, and haven’t established that there is a general policy of discrimination; it also said that the restaurants in question had lawful anti-sexual-harassment policies and practices in place.

The allegations extend far beyond Florida, however. The Nation and Type Investigations reviewed three additional lawsuits, including one filed in Texas. In that case, a man named as E.S. alleges that his 15-year-old daughter was raped by a 28-year-old coworker while working at a McDonald’s in the small city of Hearne, less than two months after she was hired in February 2023. The coworker lured her to an area behind the restaurant, then battered and raped her by a dumpster, the suit alleges.

“We never expected that something like that was going to happen,” the girl’s father told me.

The 28-year-old pleaded guilty to charges of sexual assault of a child and was sentenced to 40 years in prison. McDonald’s has denied that it bears any legal responsibility in the case, and the franchise denied “each and every” allegation made by the plaintiff. The lawsuit is set for trial in January 2026.

In the aftermath, the girl stayed home from school for about eight months, and as of December she still wasn’t speaking much to her family, her father said. “Before this happened, we used to live in a bubble where everybody in my family was safe. After this happened, it was like somebody popped that bubble.”

“I wish they can change all these McDonald’s,” he added, “so nobody can be hurt again.”

Tarnished gold:

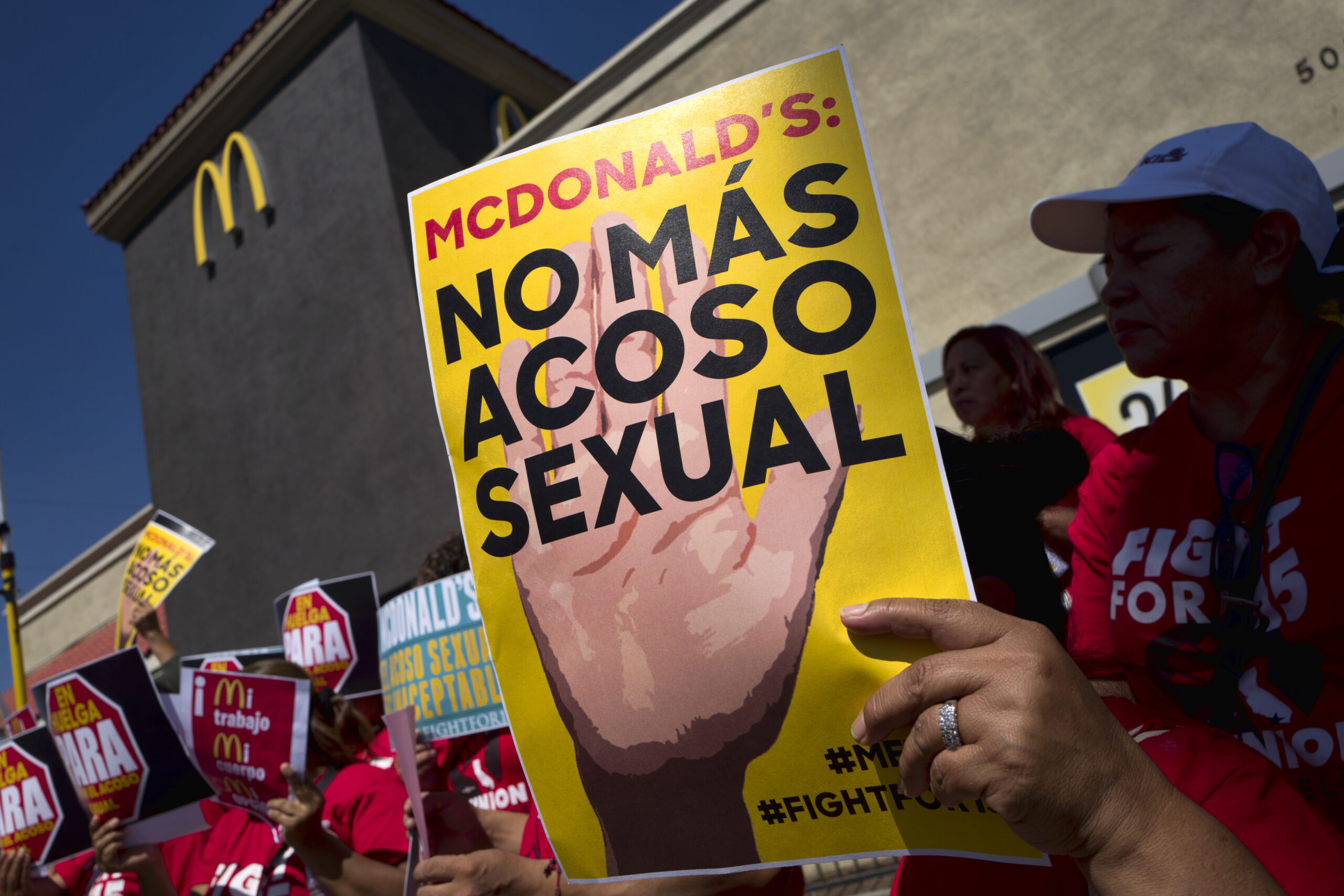

Workers and family members take part in a 15-city walkout to demand $15 an hour and freedom from harassment. Image: John Raoux / AP Photo

When McDonald’s announced its new global brand standards four years ago, it touted them as the key to eliminating sexual harassment from its restaurants. “There are no shortcuts to ensuring that people feel safe, respected and included at a McDonald’s restaurant. This work starts by taking big, intentional moves,” McDonald’s new CEO, Chris Kempczinski, said at the time.

From the beginning, however, details of what the new policies and procedures consist of have remained secret—even to McDonald’s restaurant employees. Rosalia Manuel told me that she never saw the standards, despite being a shift manager. And Eve Cervantez said she hasn’t encountered a single worker who was aware of the standards’ existence, let alone their content. When Cervantez requested that McDonald’s reveal the standards publicly as part of her lawsuit, McDonald’s argued that they must remain under seal, claiming that they are trade secrets that give the company a “competitive advantage.”

“If these are supposed to be these great standards that are going to help protect women in McDonald’s, why would they need to be under seal?” Cervantez said. A ruling on whether the details of the standards must be made public is still pending.

By choosing to keep the standards secret, McDonald’s could be limiting their effectiveness, said Vicki Magley, a psychology professor at the University of Connecticut who studies sexual harassment intervention. “There have to be consistent, distributed, accessible policies and procedures,” Magley continued. “If there is no policy that is clearly written and consistently distributed and that includes very clear procedures, then of course the employees are going to be confused.”

The problems with the standards may extend much further than secrecy, however. The “2022 U.S. People Brand Standards Visit” document lists three primary criteria that restaurants and franchises had to adhere to in order to pass an inspection by a third-party assessor. The first of these: All restaurants and franchises must have a harassment, discrimination, and no-retaliation policy in place. The second: All employees have to complete anti-harassment and anti-discrimination training within 14 days of being hired. And the third: All restaurants must have a process for employees to report harassment as well as protocols for investigating any incidents.

These criteria are reasonable starting points for implementing anti-harassment efforts. The problem is that, even when taking into account a number of additional sub-criteria outlined in the document, they lack the teeth that many experts consider necessary to combat harassment.

While the company requires restaurants to have a policy in place on sexual harassment, for instance, it doesn’t require them to have a standard way of communicating the policy to employees; according to the document, the policy can be shared via e-mail or text message, outlined in lengthy employee handbooks, or simply reviewed during orientation. The document also does not specify that the policy be written in a language that workers can easily understand or in the language that they speak.

Such fuzziness can undermine any corporate standards from the get-go, experts said. In order to be effective, anti-harassment policies must clearly explain which behaviors are prohibited, describe how to report harassment, and state what workers can expect to happen when a report is made, all in plain language that workers can understand. They can’t simply be handed out once at the start of employment, but need to be reinforced and accessible after that—posted in the break room, for example, or sent on a regular basis. The goal is not only for victims of harassment to know what to do, but also for all employees to understand “what are the behavioral expectations in the workplace,” Magley said.

It is difficult to know precisely why McDonald’s harassment prevention efforts failed in each of the cases reviewed by The Nation and Type Investigations. However, what is clear is that, at all of the restaurants in question, the new global brand standards failed to protect workers as promised.

Food, folks, and harassment:

McDonald’s CEO Steve Easterbrook before he was fired for multiple inappropriate sexual relationships. Image: AP Photo/Nam Y. Huh, File

When Fernando Valencia was hired at a McDonald’s in Vallejo, California, at the end of 2021, he didn’t receive any training, including on sexual harassment, he told The Nation and Type Investigations. This was right before the brand standards went into effect. But even after, at the start of 2022, he was given neither information nor training. Although he heard that there was supposed to be some sort of information posted in the break room about what to do if sexual harassment happened, “No teníamos nada,” he said: They didn’t have anything.

This became a problem when, shortly after Valencia started, a male store manager began harassing him daily, according to a complaint he filed with the California Civil Rights Department, touching his genitalia or making him touch the manager’s genitalia, kissing him, and promising raises for participating. Valencia had recently immigrated from Mexico and didn’t know there were laws against what he experienced, he said. “No sabía cómo eso es, cómo denunciar a eso”: I didn’t know what that was, how to report that. But it weighed heavily on him, turning his workplace into a “nightmare,” he said in Spanish. “It makes you feel small and bad about yourself.”

In June 2022, he decided to tell the manager’s boyfriend what had been happening, and the next month his hours were reduced and he wasn’t given opportunities for overtime pay, he said. It was only then that he and other employees at that location were given sexual harassment training, he said, although new hires were not.

That training was spare, Valencia said. During an eight-hour computer training on how to do the job, he said, only 30 minutes were devoted to how to talk appropriately to coworkers. The digital module warned employees not to touch each other because it could be considered sexual harassment, but it didn’t go into more detail than that. The store’s owners investigated his allegation after he filed his legal complaint, but nothing else was done about the harassment, he said.

The California Civil Rights Department declined to pursue Valencia’s case on his behalf but acknowledged his right to sue. A McDonald’s spokesperson did not respond to specific questions about Valencia’s case.

At least six other workers whose complaints The Nation and Type Investigations reviewed reported receiving no training at all after January 2022. This should not have happened, according to the “2022 U.S. People Brand Standards Visit” document. The document is clear that, in order for a restaurant to pass a brand standards inspection, assessors must ensure that it has a training program in place. The document fails to specify, however, what those trainings must consist of; nor does it require any kind of assessment as to whether they are effective or have any impact on the problem of sexual harassment.

The consequences of this lack of muscular requirements became evident in the cases of several workers who did receive training but say it was cursory and digital-only. Two workers in the Florida towns of Apopka and Lakeland who are participants in the Fairley class-action lawsuit said that the anti-harassment training they received after January 2022 consisted of slides in a PowerPoint presentation. Others watched short videos.

“The training in general felt rushed, like they just wanted me to learn how to physically do the job so that I could start working,” Salma Linda Chappa, who was hired at a McDonald’s in Plant City, Florida, in June 2022, stated in a legal filing in Fairley. It was during her orientation that a male manager started hitting on her within earshot of two other managers, who didn’t do anything to stop it, she stated. The harassment prompted her to quit a week later.

Zoe Newsome was already on edge about sexual harassment at McDonald’s before she was hired; female friends had told her they had been sexually harassed working there, she told me. But she needed the money to help her mother with bills, so in September 2021, at age 16, she began working as a crew member at a McDonald’s in Kissimmee, Florida, her first job. During her orientation, she watched a short slideshow that included basic information about sexual harassment. It “only lasted a few minutes and was not very helpful,” she wrote in a legal filing in the Fairley lawsuit.

About a year later, Newsome was promoted to crew trainer and was made to do the same sort of training, watching a “very short” video on harassment and how to report it. Neither training mentioned sexual harassment by customers, she alleges, or what to do if it happened.

Newsome told me that she’s the kind of person who “freezes up when that happens to me,” but if she had been taught what to do in the face of harassment, she might have been more prepared to handle it. “You’re young, it’s your first job, you don’t know what to do,” she said. “It’s kind of like ‘Fend for yourself.’”

McDonald’s did not comment on Newsome’s claims or those of any other worker.

While mandatory sexual harassment training via computer tutorials or videos has become common, experts say these trainings generally don’t stick with employees. “A training video coupled with a policy that’s handed to you is just wholly insufficient to change behavior,” said Gillian Thomas, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU Women’s Rights Project, who has represented sexual harassment plaintiffs against McDonald’s.

Instead, experts say, in order to be effective, anti-harassment training should be interactive, delivered by a human instead of a computer, tailored to the audience, and last at least four hours. The training should also be done regularly after people are hired, experts say. And companies should follow up with employees to see whether the training has had an impact.

Effective training is done “in a way that will actually inspire interest, inspire commitment to some kind of behavioral change,” Magley said.

McDonald’s workers protest in front of a McDonald’s restaurant in south Los Angeles on Tuesday, Sept. 18, 2018. McDonald’s workers staged protests in several cities Tuesday as part of what organizers billed as the first multistate strike seeking to combat sexual harassment in the workplace. Image: AP Photo/Richard Vogel

Training is only the first step in addressing sexual harassment. It’s equally important for employees to have channels to report incidents—and for employers to have a clear process for investigating such reports, experts say.

The “2022 U.S. People Brand Standards Visit” document specifies that restaurants have to make the details of their reporting processes “visible and easily accessible in the restaurant.” This could mean a poster with a hotline number to call with any concerns or a document outlining how to make a report. It also says that restaurants must have a protocol in place for responding to employees who report concerns, but as with the training requirements, it doesn’t specify what those protocols should be. All of the workers who reported harassment after January 2022 said nothing was done.

Ashanti Torres-Rodriguez, who was 16 when she started working at a McDonald’s in Bradenton, Florida, didn’t know what to do when a male coworker in his 40s or 50s began asking her out and making comments about her body; she had never been informed, she told me. After he touched her back one day, she decided to tell her manager, according to a legal filing in Fairley, and when he kept touching her, she reported it to two other managers and eventually to the general manager.

The general manager, who seemed to be friendly with her harasser, didn’t appear to believe her, according to her legal filing. Torres-Rodriguez doesn’t think anyone investigated, and she kept being scheduled to work with the man, who touched her for months, despite her attempts to change shifts. The experience led to frequent panic attacks—so many that her general manager threatened to fire her because they were causing her to have to leave work so often. She quit in June 2022 to get away from the abuse, taking a lower-paying job at Dollar Tree; as of a year ago, she said, her harasser still worked at McDonald’s.

Torres-Rodriguez’s experience is not uncommon. Six other workers involved in Fairley said they were told to report incidents to their managers or the general manager—but they weren’t told what to do if that person failed to act.

On her first day at a McDonald’s in Bradenton in January 2022, Marybeth Wiggins told her manager that the person training her had harassed her, but the manager responded that it was “not a big deal,” according to her legal filing. On her third day, after the person touched her butt, she reported it to a different shift manager, who suggested she wait and, if it happened again, fill out paperwork about it. After another male trainer tried to grab her breasts, she asked a manager to file an official complaint, but once again was met with indifference. “It seemed like managers just wanted the job to get done, no matter what was happening to their employees—they didn’t care if anyone was being harassed,” Wiggins wrote in a complaint in Fairley.

McDonald’s managers also appear to have been ill-equipped to deal with sexual harassment by customers. Customers sexually harassed Zoe Newsome “every few weeks,” she alleges in her legal complaint. One grabbed her wrist whenever she handed food to him. Another told her, “You look like you’re good in bed.” One man in his 50s told her, “You look like an angel, but you’re actually a bad girl,” leaving her with chills and feeling like she was going to throw up.

Early on, Newsome told her manager, who “laughed uncomfortably” and did nothing else. She kept reporting it to various managers, but they never investigated the incidents and never filed any official reports. Nothing was done. Instead, they laughed it off. “They seemed desensitized to it,” she wrote.

“I’m a workaholic, I love to work, but I didn’t feel safe,” Newsome told me. “It honestly made me hate going to work.” She quit in November 2022. “I think McDonald’s is probably the worst when it comes to sexual harassment.”

Making sure employees feel safe reporting sexual harassment is essential to combating it, experts say. Employees should be allowed to report harassment to anyone, not just specific managers. Those managers have to then be trained in how to properly deal with reports—particularly in the fast food industry, where young people are often promoted into leadership—and there have to be visible consequences for any reports found to have merit.

Another important duty of any manager is making sure those who report harassment are protected from retaliation. But four workers say that they faced consequences for speaking up.

Valencia Pratt, who worked at a McDonald’s in Miami Gardens, Florida, in early 2022, while she was pregnant, alleges in a legal filing in Fairley that a male coworker made inappropriate comments to her like “Your booty is big” and “I want to eat your front” every day. Pratt asked to be put on different shifts so she wouldn’t have to work with him; she was fired less than a week later.

Standing up for her colleagues: Rosalia Manuel protests alongside other workers demanding more significant efforts to prevent sexual harassment at McDonald’s. Image: Courtesy of Rosalia Manuel

Reducing sexual harassment is not simple, but it is also not mysterious. What it requires of employers is a concerted commitment and a determination not simply to check off items on a list but to fundamentally change workplace culture. That’s because workers’ behavior “is guided by organizational norms, by what is and is not appropriate,” said Gillian Thomas, the ACLU attorney. “The only way to move the needle on culture change is through repetition and consistency of message, and having the message come from a variety of places, including from the very top—and then building in consequences when you don’t measure up.”

Experts have provided McDonald’s with a playbook for addressing sexual harassment more effectively. In a class-action sexual harassment lawsuit filed against McDonald’s in Michigan that was settled in April 2022, the plaintiffs sought an injunction to require the company to work with employees to develop mandatory training focused on recognizing, preventing, and addressing sexual harassment in the types of scenarios actually faced by McDonald’s workers.

Their proposal would have required McDonald’s to go farther than the measures the company currently appears to have in place. McDonald’s would have had to revise its anti-harassment policies so they were in plain language; implement a well-publicized process with multiple channels for reporting harassment; develop a protocol for investigating complaints by someone “skilled in conducting and documenting workplace investigations”; and ensure that people who engage in harassment and managers who fail to intervene face consequences.

The proposal would also have required practices to prevent retaliation and a system to monitor complaints and their resolutions, plus metrics to ensure that franchises prevent harassment and are penalized if they don’t. The settlement in the case meant that McDonald’s did not have to make these changes.

Instead, for many McDonald’s workers, the current global brand standards have not done enough to keep them safe. The consequences for some have been devastating.

Rosalia Manuel hasn’t worked since she was fired from the McDonald’s in Saratoga, California, in 2022. She’s had to seek out therapy, and her depression has been hard on her four children. Her family has had to rely on her husband’s income as a cook at Google and the money the couple makes cleaning carpets on the weekends. But that still isn’t enough to cover their rent, car payments, and food.

As difficult as the situation is, however, Manuel says that it’s the lack of accountability for those who did nothing to stop the harassment that she finds most frustrating. “Saber que las personas malas estan trabajando allí me duele más,” Manuel said through sobs: Knowing bad people are working there hurts me more.